MAYAN HIEROGLYPHIC ASTRONOMY NOTES

No. 001, December 2013

Gerardo Aldana, University of California, Santa Barbara

In 1926, John Teeple cracked Page 24 of the Dresden Codex. Having puzzled over it on his long train rides between his home in New York and his chemical engineering project in California (Coe 1999:130), Teeple realized that an anomalous set of numbers recorded on this page actually provided correction mechanisms for the Venus Table of the following pages. This proved more than just insightful into ancient Mayan interpretations of Venus; it also generated what Teeple considered to be a unique opportunity. For the first time, the possibility existed of constructing an analytical solution to the Calendar Correlation problem independent of post‐Contact historical records (1926:402).

Unlike Sylvanus Morley and Herbert Spinden, who had taken up the problem before him, Teeple considered the ethnohistorical record to be untrustworthy in reconstructing a correlation between the Classic Mayan and Christian chronologies.

Any correlation based on data of early Spanish times presupposes an unbroken calendar from the time of the inscriptions—a premise that is quite doubtful and for which very little evidence could be furnished (Teeple 1931:99).

Morley too acknowledged that there were numerous inconsistencies between different alphabetic‐based historical records (1910:194). But Morley and Spinden were able to set aside the incongruities in favor of a specific subset of dates that provided them an argument for continuity.

Teeple, on the other hand, was following Joseph Goodman who believed that the inconsistencies actually revealed a situation in which different communities may have kept different calendars (1974:1). Through that perspective, one could only rely on Classic period records to find a correlation—and these would have to be astronomical. In the Venus Table, then, Teeple recognized the components he would need to find a unique solution to the problem. Specifically, he realized that if he could combine the periodicity of Venus first morning appearances with the lunar records from the Eclipse Table and the Classic period inscriptions, then he could isolate one combination that would provide an analytical solution to the Calendar Correlation Problem.

The plan really was the work of a scientist: rather than appeal to a best‐fit solution using disparate forms of data, Teeple focused on finding an analytical solution that could then be tested against other forms data. Unfortunately, the decipherment of the hieroglyphic script was still decades away, so Teeple (1926:403‐405) chose “Venus records” that turned out to be referring to other phenomena entirely. Maud Makemson, an astronomer at Vassar College, suggested a similar approach shortly thereafter (1947), but her correlation was anchored to Spinden’s argument, which shifted events 260 years earlier than Teeple’s (and Thompson’s).

Neither Teeple’s nor Makemson’s approach hit on an accurate alternative to the GMT; my reason for referring to their efforts here is that they are the same in spirit as my first attempt to address the issue. As a graduate student, I traveled to Honduras as the Teaching Fellow for the Harvard Field School at Copan. Our charge that summer was to excavate the platform of Stela 10—one of the outlying monuments patronized by the twelfth ruler of the Copan dynasty in preparation for the end of the eleventh katun (9.11.0.0.0) (Aldana 2002; Fash 1991:100112). In examining the dates on this series of stelae, I hit upon a pattern that suggested a solar periodicity within the inscribed Long Count dates (Aldana 2001; cf. Aveni 2001). I then realized that with that solar data, we would have three independent datasets to triangulate a Calendar Correlation solution: Venus phenomena recorded in the Dresden Codex; solar data in the Copan inscriptions; and the Santa Elena Poco Uinic solar eclipse record. This led me to propose a new solution to the Calendar Correlation problem; unfortunately I had not completely unpacked the assumptions that lay underneath the data I was using. For that first attempt, I used the standard model for interpreting the Venus Table, offered by Eric Thompson, Floyd Lounsbury, and Harvey Bricker (Bricker and Bricker 2007:104‐107). That model, however, was built on assumptions that I no longer consider to be tenable.

In the present iteration of formulating the problem, I follow essentially the same approach, though without the tropical year data from Copan. Here I take the fewest number of constraints necessary to generate a unique solution. These constraints must be unequivocal in their interpretation as astronomical phenomena (Aldana 2007:58‐59). The resulting analytical solution is then applied to other unequivocal astronomical data to assess the potential of the resulting correlation constant.

The first anchor that I take as unequivocal is the Poco Uinic Stela 3 eclipse record, occurring on 9.17.19.13.16. While there have been questions raised periodically about the iconography of the “eclipse glyph,” the record fits without complication as a potential eclipse relative to the Lunar Series data we have from Classic period inscriptions and relative to the Dresden Codex Eclipse Table.

Next, I take the Venus record in Copan Structure 10L‐11 as a record of an actual observed event. Andreas Fuls (2008) and I (2011:34) have already shown that the Copan record fits very well with the Long Counts in the Dresden Codex Venus Table. In fact, the Copan record suggests that the anchor of the Venus Table is not a numerological contrivance as others have proposed (Lounsbury 1983; Bricker and Bricker 2007), but a record based on observation (Aldana 2011:37). This means that if we start with the hieroglyphic texts themselves, the Copan record and the Venus Table records together suggest that they are only providing historical observations. It is only when 20th and 21st century scholars have introduced the needs of the Calendar Correlation Problem that an “error” was proposed (of 16 days) for the base of the Venus Table, leading to hypotheses of contrivance, “entry” versus “base” dates, etc. (Aldana 2009).

In any case, with a Venus progression and an eclipse record, we now have an interval between an eclipse and a Venus first morning visibility event (fmv or “heliacal rise”) independent of any correlation. This is key: we have two independent astronomical events defining an interval just between Long Count dates. This allows us to run Venus synodic periods forward from the anchor date to see where Venus should have been in its cycle on the Poco Uinic eclipse date. The interval of interest, then, is: 9.17.19.13.16 ‐9.9.9.16.0 = 61156 days = 104 VR + 428 days, i.e. the interval between the base of the Venus Table and the Poco Uinic eclipse date is 104 Venus Rounds and 428 days into the next Venus Round. This would put Venus in the middle of its evening star visibility at the time of the eclipse. We can therefore look through the historical record of eclipses to find one with an appropriate Venus position, and we will have an analytical solution to the problem.

It is worth noting that this method would have worked for Teeple and Makemsom while they were mulling over the problem. They, however, had no additional data to constrain the problem independent of astronomical inference. Makemson, for example, considered all eclipses falling within a 500‐year period (1946:26). Not long after their time, though, radiocarbon data began contributing significantly to the scope of the problem (Thompson 1972; Ralph 1965; Satterthwaite and Ralph 1960). And even more recently, Douglas Kennett and colleagues (2013) have suggested a tremendous narrowing of the window of opportunity for a solution. That is, we have known since the 1960s’ work of Elizabeth Ralph and Linton Satterthwaite that the GMT was corroborated by radiocarbon dates—i.e. that events datable through both hieroglyphic records and 14C samples resulted in the former lying within 1‐σ uncertainty of the latter (Sattherthwaite and Ralph 1960; Ralph 1965). But Kennett et al. have introduced new techniques (AMS and Bayesian statistics) to narrow the uncertainty for 14C‐dated artifacts. Their results place the GMT at the early end of the new 14C probability distribution that they generate (2013:3). In other words, they re‐corroborated the GMT using AMS data, but at the same time, they also imply that—depending on the weight given to that AMS data—a more accurate Calendar Correlation constant might be up 20 to 40 years later.

| Eclipse Date | Visibility in Region | Venus Round Position |

|---|---|---|

| 725/1/19 | N | Y |

| 726/5/13 | Y | N |

| 729/10/27 | N | Y |

| 734/8/3 | N | Y |

| 736/6/13 | Y | N |

| 739/4/12 | Y | N |

| 742/8/5 | N | Y |

| 743/7/25 | Y | N |

| 744/1/19 | Y | N |

| 747/5/14 | N | Y |

| 750/3/12 | Y | N |

| 750/9/5 | Y | N |

| 761/2/9 | Y | N |

| 765/11/17 | Y | N |

| 768/3/23 | N | Y |

| 772/1/9 | Y | N |

| 772/12/29 | N | Y |

| 777/10/6 | N | Y |

| 783/6/4 | Y | N |

| 785/10/8 | N | Y |

| 790/7/16 | Y | N |

| 797/8/26 | Y | N |

| 798/2/20 | Y | N |

| 798/8/16 | N | Y |

| 803/5/24 | N | Y |

| 805/9/26 | Y | N |

| 811/5/26 | N | Y |

| 815/3/14 | Y | N |

| 820/12/9 | N | Y |

| 826/2/10 | Y | N |

| 828/12/10 | Y | Y |

| 830/5/25 | Y | N |

| 833/9/17 | N | Y |

| 837/7/6 | Y | N |

| 846/7/27 | N | Y |

| 847/12/11 | Y | N |

| 851/9/28 | Y | N |

| 854/7/28 | N | Y |

| 855/7/17 | Y | N |

| 856/1/11 | Y | N |

| 859/10/29 | Y | N |

Table 1: Potential Eclipse candidates for the Poco Uinic St. 3 record.

Suffice it to say that contrary to the position of Teeple and Makemson, we can now use radiocarbon data to set reasonable boundaries for our search through eclipse histories. Being generous (i.e. including more data than necessary), we may take the GMT as the nominal radiocarbon probability distribution mean, and then propose that any acceptable alternate solution will lie within plus‐or‐minus 75 years of it. Since we don't know if the GMT is early or late within the 14C uncertainty, this approach is certainly justifiable. The next step is to take up the task of looking through NASA's database for all solar eclipses within 75 years of 7/16/790—the GMT translation of the Poco Uinic eclipse. I tabulated all of these in a spreadsheet, and then ran forward Venus synodic periods through this window of eclipse events looking for anything that might be close to the phase predicted by the Long Count interval. (See Table 1) Should an acceptable candidate have emerged at that point, it could be checked against the Dresden Codex Eclipse Table and against tropical year records from Classic period inscriptions. I consider no other records from the Classic or Postclassic periods as unequivocally dated astronomical records.

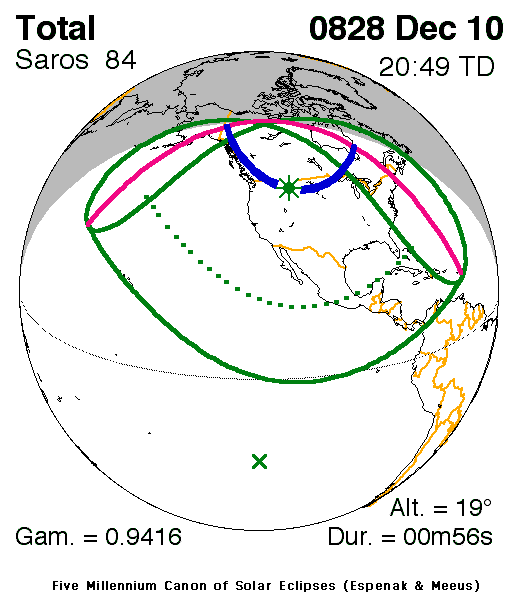

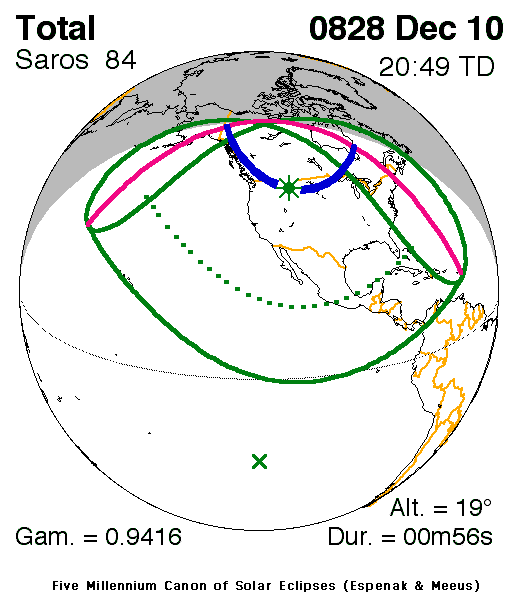

The only eclipse visible in the Mayan region fitting the two constraints (i. appropriate Venus phase; and ii. within 14C uncertainty) occurred on 828/12/10. This result actually suggested a slight advantage over the GMT since a December eclipse event seemed much more likely to have been visible than one in July—the middle of the rainy season. On the other hand, the 828 eclipse was not “total” at the latitude of Santa Elena Poco Uinic. (See Figure 1) This set up a potential concern: is it more compelling for the eclipse to have been total during the rainy season or partial during the dry season? Unfortunately the hieroglyphic inscription does not provide any further description to help us make a distinction. It is worth noting, though, that multiple eclipses visible in the region occurred within a span of 15 years, and we have no hieroglyphic records of them. (See Table 1) It would seem, therefore, that the reason for noting the Poco Uinic eclipse was not simply that one occurred—it must have been tied to a local historical event with meaning to inhabitants of the city, despite it not being maintained for us.

Without a clear reason to dismiss the 12/10/828 eclipse event, and with its potential advantage, I then computed the resulting Correlation Constant as 598,313. This constant (which I call ATM or “Aldana’s Constant”) I applied to the Dresden Codex Eclipse Table.

Although it may not be well known outside the archaeoastronomy community, the interpretation of the Eclipse Table is not straightforward. On the one hand, scholars have been divided over whether it was intended to record historical eclipses, or whether it was to be used as a warning table (Aveni 2001:173; Bricker and Bricker 2011:261‐275). Beyond this complication, though, there is the further issue that with the GMT, none of the Long Count dates in the Eclipse Table actually corresponds to an eclipse visible in the Mayan region. Again, just as the GMT does not put the anchor of the Venus Table on a heliacal rise of Venus, neither does it put any of the potential anchors of the Eclipse Table on an eclipse date. Scholars have proposed various schema for handling this complication (Bricker and Bricker 2011:276), but they all acknowledge that a table intended to track eclipses does not actually have a base situated on one. With the new correlation constant, however, this complication goes away. With ATM, an eclipse visible in the Mayan region does occur on one of the base dates.

The Preface to the Eclipse Table (on Pages 52) lists three Long Count dates separated by intervals of 15 days. The purpose of 15‐day intervals relative to eclipse phenomena is straightforward as noted by Bricker and Bricker: ‘Eclipses tend to go in pairs or threes: solar‐lunar‐solar. A lunar eclipse is always preceded or followed by a solar eclipse (two weeks in between them)’ (Duffett‐Smith 1981:155). We have quoted this statement of a twentieth‐century astronomer because it expresses precisely the model used by the authors of the eclipse table in the Dresden Codex… (2011:55).

Makemson, too, states: “[a]s these dates are fifteen days apart, they may be reasonably interpreted as the times of two solar eclipses with a lunar eclipse halfway between” (1947:25). ATM puts the middle of three dates (9.16.4.11.3) on a lunar eclipse readily visible in the Maya region (794/4/20). This means that a correlation constant derived only to capture the position of Venus on the date of the eclipse recorded at Poco Uinic also newly aligns the preface to the Dresden Codex Eclipse Table with expectation.

Furthermore, a visible lunar eclipse works well because it suggests that the author of the table had this as a historical record, and then computed the two possible solar eclipse dates (15 days before and after, within an eclipse season), which s/he might then use to project forward and construct the table proper. The anchor in this reading, through 598,313, is the lunar eclipse; the computation made by the scribe is for solar eclipse nodes; and the Table itself is intended to project forward from that point on.

Since it now made better sense of the Eclipse Table, I felt compelled to check the new correlation constant against what I have argued in the past are solar year partitions within the hieroglyphic inscriptions, marked by K’AL‐K’IN verbs (Aldana 2001). These records—also independent of calendar correlation—are separated by quarter‐tropical‐year intervals, spanning the entire Classic period—i.e. from the Early Classic E‐Group stelae at Uaxactun, to the Terminal Classic inscriptions at Chich’en Itza. ATM puts the Uaxactun E‐Group stela dates on June 23, which is easily within the observational tolerance of a summer solstice. (The GMT puts them on February 3, which is not close to any of the quarter‐year partitions.)

Because it is built on the eclipse event at Poco Uinic, it carries along all of the Lunar Series data as well as the GMT. The new correlation constant thus meets all of my own tests for the best‐understood astronomical records of the Classic period. It actually does a better job of providing reasonable interpretations for the bases of the DCVT and the DCET (qua bases), and for /k’alk’in/ events. This led me to consider one pseudo‐record that has always intrigued me.

Piedras Negras Stela 10 carries that famous accession motif Tatiana Proskouriakoff used to present her historical hypothesis and thus revolutionize the study of Mayan hieroglyphic writing. Within the skyband in that motif there is what looks like a comet: EK’ attached to K’AHK’/BUTZ’. The word “comet” is attested in Yucatec as butz’ ek’, so I’ve often wondered if a comet observation attended some aspect of Ruler 4’s accession on 9.14.18.3.13 (b. 9.13.9.14.15). The GMT offers no compelling possibilities, but ATM gives us Halley's Comet showing up on 9.14.10.3.10, another comet observed by Chinese astronomers on 9.14.16.17.2, and finally a hugely impressive comet (according to Chinese records) visible during the year of 9.15.0.0.0 itself (on 9.15.0.7.12)—all of which are quite near the 9.15.0.0.0 period end commemorated by Piedras Negras Stela 10 (Williams 1871:197).

The main point of this essay—and the appeal to Teeple and Makemson—is that it presents an analytical solution to the Calendar Correlation problem first, with corroborating records following. It is not a best‐fit solution, either statistically or through data rationalization. With the exception of the comet record, none of the astronomical records used to generate the constant or to test it is ambiguous or implicit.

Also compelling with this solution is that it changes the representation of the scribes behind the records that we do have. Under 598,313, the base dates for the Venus Table and the Eclipse Table are no longer numerological contrivances; now they are both historical records, preserved and utilized along with later observations— probably made by the scribes themselves—to construct Mayan models of planetary motion.

Aldana, G. 2001, “K’in in the Hieroglyphic Record: Implications of a Pattern of Dates at Copan, Honduras” Mesoweb:

Aldana, G. 2002, “Solar Stelae and a Venus Window: science and royal personality at Classic Maya Copan” in Archaeoastronomy Supplement to the Journal for the History of Astronomy, 27 (JHA, xxxiii (2002)), S30‐S50.

Aldana, G. 2007, The Apotheosis of Janaab’ Pakal: Science, History, and Religion at Classic Maya Palenque. University Press of Colorado, Boulder.

Aldana, G. 2011 Tying Headbands or Venus Appearing: new translations of k’al, the Dresden Codex Venus Pages and Classic period royal ‘binding’ rituals. BAR International Series 2239, Archaeopress, Oxford.

Aveni, A. 2001, Skywatchers: Revised Edition of Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico University of Texas Press, Austin.

Bricker, H. and Bricker, V., 2007, “When was the Dresden Codex Efficaceous?” in C. Ruggles and G. Urton (eds.), Skywatching in the Ancient World: New Perspectives in Cultural Astronomy Studies in Honor of Anthony F. Aveni. University of Texas Press, Austin, 95–120.

Bricker, H. and Bricker V. 2011 Astronomy in the Maya Codices. American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

Coe, M. 1999, Breaking the Maya Code. Thames and Hudson, London.

Espanek, F. 2013, NASA Eclipse Website. http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse.html

Fash, W.L. 1991, Scribes, Warriors, and Kings: the city of Copan and the ancient Maya. Thames and Hudson, London.

Fuls, A. 2008, “Reanalysis of Dating the Classic Maya Culture,” Amerindian Research, Band 3/3, Number 9, 132–146.

Goodman, J. T., 1974, Appendix to A. P. Maudslay Archaeology, Volume VI Milpatron Publishing Corp., New York.

Kennett, D.J. et al. 2013, “Correlating the Ancient Maya and Modern European Calendars with High‐Precision AMS 14C Dating.” Scientific Reports 3, 1597; DOI:10.1038/srep01597.

Lounsbury, F. 1983, “The Base of the Venus Table of the Dresden Codex, and its Significance for the Calendar‐Correlation Problem,” in A. F. Aveni and G. Brotherston (eds.), Calendars in Mesoamerica and Peru: Native American Computations of Time, BAR International Series 174 Archaeopress, Oxford, 1–26.

Makemson, M.W. 1947, “The Maya Calendar” in Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Vol. 59, No. 346, 17‐26

Morley, S.G. 1910, “The Correlation of Maya and Christian Chronology” in American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 14, no. 2, 193‐204

Ralph, E.K. 1965, “Review of Radiocarbon Dates from Tikal and the Maya Calendar Correlation Problem,” in American Antiquity 30, 4, 421‐427.

Satterthwaite, L. & Ralph, E. K. 1960, “New radiocarbon dates and the Maya correlation problem,” in American Antiquity. 26, 165–184.

Teeple, J.E. 1926, “Maya Inscriptions: the Venus calendar and another correlation,” in American Anthropologist, n.s. 28, 402‐408

Teeple, J.E. 1931, Maya Astronomy, Contributions to American Archaeology, Volume I, Nos. 1 to 4 Carnegie Institution, Washington.

Thompson, J.E.S. 1971, Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: An Introduction. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Williams, J. 1871, Observations of Comets, from B.C. 611 to A.D. 1640, extracted from the Chinese Annals. Strangeways and Walden, London.