https://mayadecipherment.com/2012/05/02/the-misunderstanding-of-maya-math

May 2, 2012

David Stuart

A great many descriptions of ancient Maya mathematical notation read something like this:

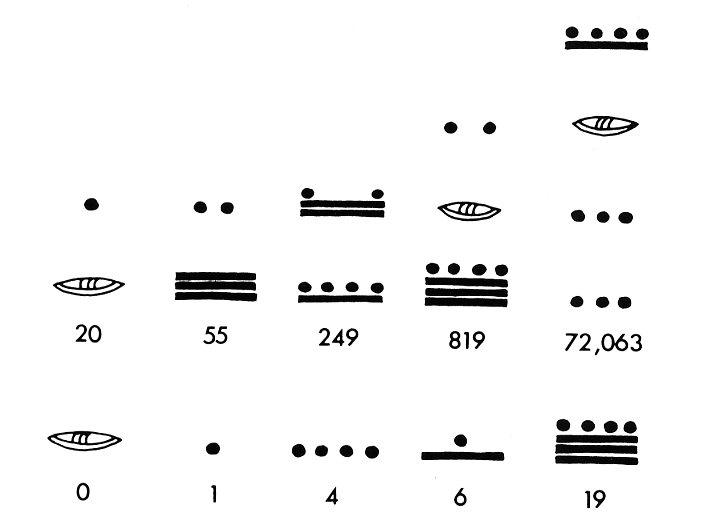

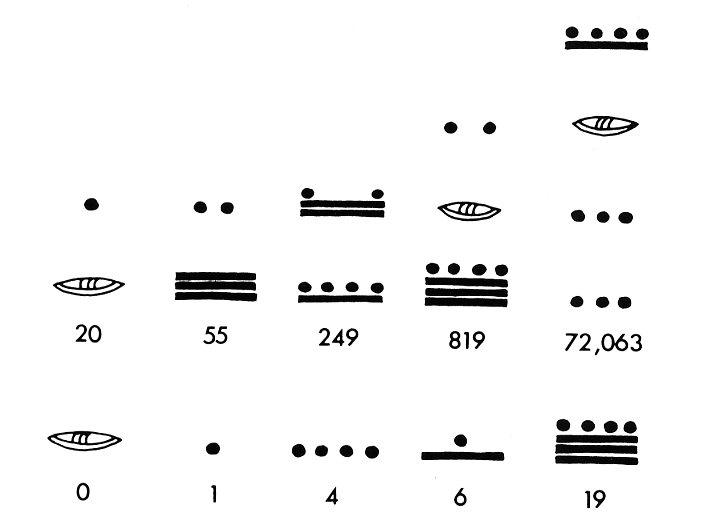

The Maya made use of a base-20 (vigesimal) system with the units of 1, 20, 400, 8,000, 160,000, etc.. To write a number, a scribe would show multiples of these units in a set columnar order, moving down from highest to lowest, and add them accordingly. "32" for example would be written as single dot for 1, representing one unit of 20, above the two bars and two dots for 12, corresponding to the "ones" unit (1×20 + 12×1 = 32). A larger number such as 823 would be written in three places as two dots followed by one dot followed in turn by three dots, standing for the necessary multiples of 400, 20, and 1 respectively (2×400 + 1×20 + 3×1 = 823).

Similar descriptions of Maya math pervade the literature, textbooks and the internet. For example Michael Coe writes in the latest edition of The Maya (p. 232):

Unlike our system adopted from the Hindus, which is decimal and increasing in value from right to left, the Maya was vigesimal and increased from bottom to top in vertical columns. Thus, the first and lowest place has the value of one; the next above it the value of twenty; then 400; and so on. It is immediately apparent that "twenty" would be written with a nought in the lowest place and a dot in the second.

The illustration accompanying this text provides many examples of this purely vigesimal system:

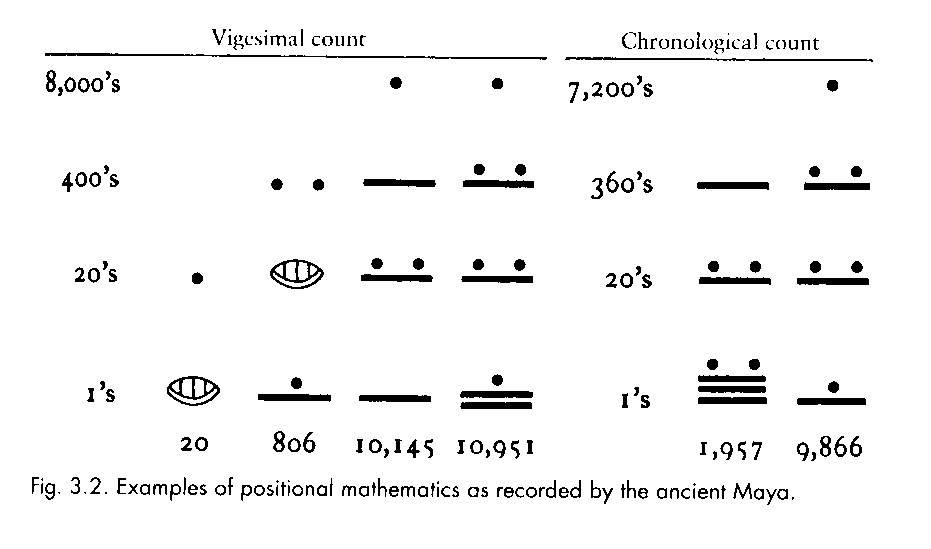

Maya mathematical notation is described the same way in a number of other influential books widely read in classrooms and seminars, such as The Ancient Maya: New Perspectives (McKillop 2004:277) or the venerable The Ancient Maya (Sharer and Traxler 2006:101). In the latter work, two types of counts are represented (see below) – the purely vigesimal or base-20 count (with units of 1, 20, 400, and 8,000) alongside what’s called the "chronological count" (with units of 1, 20, 360, 7,200). The second is of course the basis for the familiar Long Count system.

The illustration accompanying this text provides many examples of this purely vigesimal system:

A big problem exists with all of these seemingly straightforward descriptions of Maya mathematical notation. As far as I am aware no purely vigesemal place-notation system was ever written this way. It’s true that in Mayan languages numbers are base-20 in their overall structure, just as in most Mesoamerican languages. In Colonial Yukatek, for example, we have familiar terms for these units: k’al (20), bak’ (400), pik (8,000), and so on. However, ancient scribes never represented these units in a columnar place notation system, as is so commonly described in the textbooks. That format was instead always reserved for a for the count of time, in what we know as the Long Count. That system is mostly vigesimal, but it is skewed in one of its units (the Tun, of 360 days) in order to conform as much as possible to the number of days in the solar year (365). To reiterate: the columns of numbers we find in the pages of the Dresden Codex or painted on the walls of Xultun (stay tuned, folks…) are all day counts; the positional notation system was never used for reckoning anything else.

In the ancient inscriptions non-calendrical counts using large numbers are quite rare, mostly found in connection to tribute tallies, such as the counting of bundled cacao beans. But in those settings the scribes always seem to show nice rounded numbers (as in ho’ pik kakaw, "5×8,000 [40,000] cacao beans," shown in the murals of Bonampak) without all the place units we know from the Long Count. In the Dresden and Madrid codices, counts of food offerings are given as groupings of WINIK (20) signs with accompanying bars and dots for 1-19. In this way a cluster of four such elements (4×20) with 19 writes 96 (See Love 1994:58-59; Stuart, in press).

There is a good deal we still don’t know about the ways the Maya wrote quantities, especially of non-calendrical things. The pattern nonetheless seems clear that the place notation system of the Long Count was restricted to time reckoning, and never applied to the purely vigesimal counting structure we see reflected in Mayan languages. The descriptions of written numbers found in the many texts about the ancient Maya therefore need to be corrected.

Coe, Michael. 2011. The Maya (8th edition). Thames and Hudson, New York.

Love, Bruce. 1994. The Paris Codex: Handbook for a Maya Priest. University of Texas Press, Austin.

McKillop, Heather. 2006. The Ancient Maya: New Perspectives. W.W. Norton, New York.

Sharer, Robert, and Loa Traxler. 2005. The Ancient Maya (6th edition). Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Stuart, David. In press. The Varieties of Ancient Maya Numeration and Value. To appear in The Construction of Value in the Ancient World, ed. by J. Papadopolous and G. Urton. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA, Los Angeles.

Stanley Guenter

May 2, 2012 / 7:18 PM

Dave, I am curious as to how you would explain the numerals on K1196. While it is not clear what is being counted I would find it very difficult to think that this is any kind of calendrics, given the absence of any glyphs marking such and the fact that there are both more or fewer glyphs than necessary for a Long Count date. I suspect one of the reasons for the absence of large mathematical counts in the texts we have is genre, and that Classic period codices would almost certainly have included tribute lists such as we have for the Aztecs. I suspect that the pattern you have identified, which is definitely very strong, is due to the fact that of the types of things the Maya would have counted in large numbers, only time periods were the sorts of things the Maya recorded regularly in monumental inscriptions that have survived to the present. Vase inscriptions normally don’t include Long Count dates, I would note, and again, I think there is an interesting correlation between types of information recorded and the medium of the inscription. Very interesting post!

David Stuart

May 3, 2012 / 4:41 PM

Gracias, Stan. K1196 shows a deity reading off numbers from a book, but who can say what’s being counted? There’s a rough sequencing to the numbers, so I kind of doubt it’s a Long Count or calendrical. As yes, of course, tribute tallies were no doubt recorded in the perishable documents. As you mention, I suspect the Classic Maya would have tallied their tribute items in ways similar to what we see in the Codex Mendoza, where everything is carefully divvied up in units that are multiples of base-20 system. For the Nahua, that type of number writing was never really applicable to the representation of dates and chronology, either.

Nick Hopkins

May 2, 2012 / 10:07 PM

The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. In the living Mayan languages we have numerous documentations of number systems, and they use straight-forward vigesimal intervals. See Tozzer’s Maya Grammar for an early attestation, and for the whole family, Yoshiho Yasugi, Native Middle American Languages, An Areal-Typological Perspective, Senri Ethnological Series, 39, pp. 303-333. National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka, 1995. While it may be true that the only written evidence of large numbers is calendrical and not strictly vigesimal, there is no reason to believe that strict vigesimal systems were not in use in other domains of culture. Maya calendrics is not all there was to Maya math.

David Stuart

May 3, 2012 / 4:25 PM

Hi Nick. Perhaps I wasn’t clear enough in my post, but I certainly don’t claim, and would never consider, that straight vigesimal counting was absent in the ancient sources. On the contrary, we’ve known for a number of years that vigesimal numeration is in the glyphs, as in the example I mentioned with the non-calendrical uses of the PIK logogram for 8,000. I suspect a logogram for B’AK’ ("400") is out there too somewhere, but as yet not securely identified (I have an idea on that, though). My basic point was that we have no evidence that the vigesimal system, so basic to Mesoamerican languages, was ever expressed using the Long Count format, a somewhat quirky and archaic system reserved for expressions of deep time. So, while there’s evidence of straight vigesimal numeration in the script, as one would expect, there’s no reason to think they wrote those numbers as described in the current textbooks. Put simply, people have long assumed that a straight vigesimal LC system existed, without any actual examples in hand. The hints of base-20 counting we do see in the script look different.

Stephen Chrisomalis

May 3, 2012 / 2:39 AM

It’s striking how resistant some scholars are (Mayanists and non-Mayanists alike) to this argument. When I argued along these lines in my comparative volume, Numerical Notation (Cambridge, 2010), several peer-reviewers were deeply offended, as if I had suggested that a lack of evidence for positional counts of anything other than time was an ethnic slur. It really is striking, to a non-Mayanist from a comparative perspective, that there really is no positional counting of large numbers of anything other than time – which I don’t think can be easily explained by genre.

Stephen Houston

May 3, 2012 / 1:03 PM

Nick Hopkins has made a good argument for theism!

But, seriously, Dave is simply saying that, in Maya script, columnar place notations record time, but are not employed in other enumerations in the glyphs. He is not making a statement about Mayan language or its contents; his thoughts reflect the graphic presentation of numbers. (Note his words above: the "place notation system of the Long Count was restricted to time reckoning, and never applied to the purely vigesimal counting structure we see reflected in Mayan languages.")

Also, K1196 is, in my view, a sequence of consecutive #s (albeit with odd disjunctions), not a place notation: 7, 8, 9…12, 13…11.

Anna Blume

May 4, 2012 / 12:57 AM

Also of interest when we begin to rethink Maya numerals and the customary ways in which we transcribe, translate or interpret them is the question of "mi" and "chum": zero and seating. The custom of writing "chum" as zero is misleading and confounds two related but distinct concepts. I look forward to your essay very much.

Christian Prager

May 5, 2012 / 12:19 PM

Hi all,

you might be interested in reading this paper by Gen Le Fort and Bob Wald (1995) who discuss the use of non-calendaric numbers in Classic Maya inscriptions on the basis of NAR St. 32.

1995 Large Numbers on Naranjo Stela 32. Mexicon 17:112-114.

follow this link to download this mexicon article: vma.uoregon.edu/Mexicon/xvii6wald.pdf

Greg Reddick

May 9, 2012 / 7:43 AM

It is my belief that the primary unit that the Maya counted by was the tun, not the kin. If you view it that way, the Maya representation of time is strictly vigesimal. There are two different units that are involved, tuns and days within tuns. Both are strictly vigesimal, but the days max out at 359.

We have a parallel in how we count time: hours and minutes, like 2:24. The hours are one count that is done in decimal, and the minutes are another count that is done in decimal (not really base 60) as well, with the minutes maxing out at 59.

If you wrote a long count as 9.16.7:3.4, with a colon between the 7 and 3, it would make that more obvious. When doing the calendar math, you would add the tuns separately from the winals and kin, then carry multiples of 360 kin into the tuns.

I am not unique in thinking this way. Goodman, Gates, Teeple, and Thompson had the same impression (Thompson, Maya Hieroglyphic Writing, pp 141-142). Thompson gives six reasons why he thinks this is the right way to represent days, including that the main element of the ISIG is a tun sign.

David Stuart

May 9, 2012 / 2:09 PM

Hi Greg, Thanks for your comment. Of course you are correct. I discuss the same point in The Order of Days (p. 168), noting that the basic unit of the LC system is the Tun, since the counts above it are purely vigesimal. I suppose this is what has thrown people off for so long in thinking about how the Maya wrote straight vigesimal (non-calendrical) counts.

Karla

July 9, 2012 / 11:25 PM

Hi David, I would like to know if there is a maya name for the long count calendar? And if 13.0.0.0.0 is the first day of the long count, is 0.0.0.0.1 the second day?

David Stuart

July 16, 2012 / 7:25 PM

Hi Karla,

We don’t know the ancient name for the Long Count itself, although there must have been one.

The day after 13.0.0.0.0 was 13.0.0.0.1, and the bak’tun after was 1.0.0.0.0.

Greg Reddick

July 16, 2012 / 8:17 PM

David, what evidence is there for 13.0.0.0.1 being the long count after 13.0.0.0.0? In Appendix 4 of Linda Schele’s Maya Glyphs:The Verbs is a pretty good list of dates in the Maya Corpus (anyone know of a better one?). It list two dates in the period from 13.0.0.0.0 to 1.0.0.0.0: 13.0.1.9.2 from the Temple of the Cross and 13.4.12.3.6 from the Temple of Inscriptions (west). In both cases, I think they are represented as calendar rounds and not actual long counts (and context resolves the dates). As far as I know, we don’t actually have any long counts written in that first bak’tun of this era, so we don’t know how the Maya would have written them.

I think the Maya themselves punted on the question by just writing them as distance numbers or calendar rounds. I actually had a one minute discussion with Linda about this, and as far as she knew there weren’t any long counts in that period and that the question hadn’t been answered. However, I am not up on all the inscriptions found recently, so are there are other inscriptions that resolves how the Maya represented dates in the first bak’tun?