The radar coverage of the United States airspace is nearly complete. In particular the northeastern area, where all four hijackings took place on 9/11, has no “gaps” whatsoever in radar coverage. Nonetheless there was radar loss on 9/11 with respect to the third hijacked plane, American Airlines Flight 77, which was reported to have hit the Pentagon.

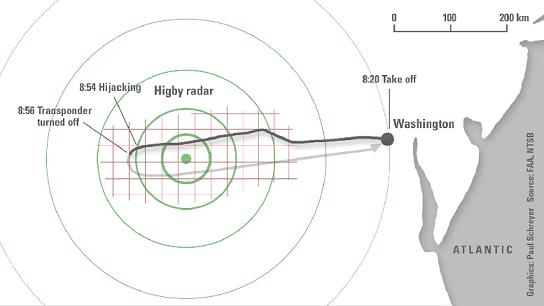

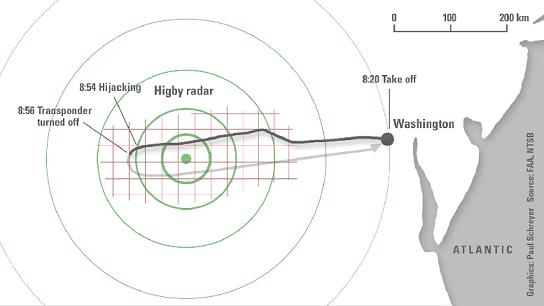

American 77 took off at 8:20 a.m. EST and was hijacked more than half an hour later. It began to change its course at 8:54 and, while slowly turning to the left, its transponder was switched off at 8:56. (1) Until then it had been displayed on the radar scopes of air traffic control via the Higby radar site. This was a “beacon-only” site, meaning a site that could only display transponder signals. When American 77´s transponder was turned off, the plane was no longer visible to Higby radar. (2)

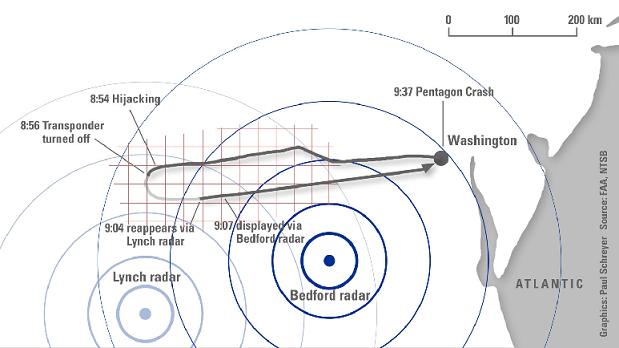

Nonetheless the area was covered by additional radar sites. (3) Several sites that were not “beacon-only” tracked American 77 after its transponder had been turned off. However the plane was lost to controllers because of the way computers processed the radar data – and because of an unexplained wide-ranging radar failure.

For the computer managing the incoming radar data, the airspace is divided into “radar sort boxes” (illustrated by the red grid in the map above). Each sort box is 16 nautical miles wide and each is assigned to a single radar site. Additionally each sort box is assigned to a second “supplemental” radar site for safety. If the first assigned site is declared to not work properly, for example because it is taken down for maintenance, the computer starts to display the data from the supplemental site on the controller´s scope. The data from all other radar sites covering the area of the sort box is rejected and not visible at all to air traffic controllers. This computer process is called “selective rejection”. (4)

Unfortunately, the exact assignments for the radar sort boxes crossed by American 77 during its flight are not publicly available. As former air traffic controller Tom Lusch, an expert on the problem of “selective rejection,” pointed out: “Missing is the information that informs us how the radar sort boxes were adapted.” (5) It is also unclear if the 9/11 Commission ever obtained those specific records. However, the assignments can also be estimated from the distance of the nearest radar sites to the specific sort box if it is assumed that the nearest long range radar sites would always be assigned to a sort box.

The specific sort box that American 77 was crossing when the transponder was turned off was assigned to the Higby radar site. Supplemental to this was the Lynch radar site (see map below). This precise information is not an estimate but was reported by the FAA. (6)

Thus, when the controller lost the transponder signal and switched to “primary radar” on his scope, the computer started displaying the radar data received from Lynch. The problem: Lynch operated poorly. For unknown reasons it did not “see” American 77 in the precise area where the transponder was turned off. That is why the plane got lost for about 8 minutes, exactly when it turned.

The problem with the Lynch radar site was known to air traffic controllers and managers at the Indianapolis Air Route Traffic Control Center (Indy Center) before 9/11, as interview notes by the 9/11 Commission reveal. (7) However, the Commission apparently failed to investigate why Lynch operated so poorly and also why the FAA, being in charge of the radar sites, had allowed this.

In fact, planes do disappear temporarily from radar from time to time for a number of technical reasons. Yet the instance of turning off a transponder in a small zone, internally assigned to a supplemental radar site which is known to insiders to be faulty, appears suspicious.

American 77 reappeared on the scopes of Indy Center only at 9:04 via Lynch radar site. At 9:07, the plane apparently crossed into a sort box that was assigned to the Bedford radar site and was subsequently displayed via Bedford without a problem. (8)

It is also worth mentioning that Flight 77 did not turn off its autopilot while being hijacked. Instead the autopilot was functioning throughout the radical change in course back to Washington. It stayed on until approximately 9:08 when it was shut off for three minutes and turned on again. (9)

Now, what are the conclusions? Miles Kara, who investigated the issue for the 9/11 Commission, said that he was also intrigued by the location of the turn initially. However he is convinced that it was not more than a coincidence. (10) Nonetheless, an important question is why the alleged hijackers waited for more than half an hour before they took over and turned the plane. One can only guess because there is no clear explanation for this behavior. One thing is very obvious, however: the earlier the plane would have been turned, the more likely the plot would have been successful. Why wait for more than 30 minutes, while flying away from the intended target? For example, American Airlines Flight 11 was apparently hijacked only 15 minutes after take-off.

On the other hand, it is clear from investigating the radar sort box programming that American 77 would have remained completely visible to air traffic control if it had turned 6 to 8 minutes before or even earlier.

Were the alleged al Qaeda hijackers aware of this? We do not know, but probably not. At least there is no evidence for any contact between al Qaeda operatives and insiders with knowledge of the Lynch radar gap. Could some planners outside al Qaeda have known? Yes, this is possible. As mentioned, the information was not public, but was available only to insiders before 9/11.

Therefore it all depends on a specific interpretation: Was the location of the turn a coincidence or not? Disappearing from radar screens actually was essential for the success of the terrorists’ mission. What would have happened if the plane had not become lost to controllers at 8:56?

First, air traffic control would have observed the full 180-degree turn of American 77. At 9:00 it was heading east. For the past five minutes controllers had tried to contact the plane via radio without success. So there was loss of communication and the plane was dramatically off course. Additionally the transponder signal had disappeared. Altogether, 9:00 a.m. would have been the appropriate time to alert the military and call for the scrambling of fighter jets. In reality this had not happened only because, without any radar signal, controllers had apparently thought that the plane had crashed.

If the military had received the call at 9:00, Langley Air Force Base would have been able to get fighters in the air at about 9:15. This was the case at Otis Air Force Base, where NEADS had received a call at 8:38 and the jets were in the air at 8:52. If the Langley jets had taken off at 9:15, they would have been vectored to American 77 and would have reached the plane then at approximately 9:27 – about 10 minutes before it crashed.

It is doubtful if a shoot-down order could have been issued by that time. But at least – and the following fact is constantly underestimated – the fighter pilots could have taken a deep look into the cockpit of the hijacked plane to see who was actually at the controls. This would have helped to confirm if it really was Hani Hanjour, the alleged pilot, who reportedly could not even fly a Cessna safely, and whose presumed boarding is not backed by any airline check-in data. (11)

But that did not happen because of the loss of radar precisely at the turning point of American 77.

About the author: Paul Schreyer, born 1977, is a German author and journalist, writing for the online journals Global Research, Telepolis, and others. He is author of the book “Inside 9/11.” At the Journal of 9/11 Studies he previously published the paper “Anomalies of the air defense on 9/11,” in October 2012. His website is www.911-facts.info.

[1] 9/11 Commission Report, pp. 9, 25

http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf

[2] FAA Memorandum “AAL 77 Flight Path Information,” 17.09.01

http://de.scribd.com/doc/13950396/T8-B3-FAA-Gl-Region-Fdr-AA-77-Radar-Info-Emails-Withdrawal-Notice-Memo-and-Questions

[3] Tom Lusch´s Website, June 2010

http://tomlusch.com/tomlusch/tomlusch/AAL77.html

[4] “Selective Rejection of Low Altitude Radar Data at Air Route Traffic Control Centers: An Unsatisfactory Compromise,” 26.09.1988, Thomas G. Lusch

http://www.tomlusch.com/tomlusch/tomlusch/index_files/SelRej.pdf

[5] Email from Tom Lusch, 11.01.13

[6] FAA Memorandum „AAL 77 Flight Path Information“, 17.09.01

http://de.scribd.com/doc/13950396/T8-B3-FAA-Gl-Region-Fdr-AA-77-Radar-Info-Emails-Withdrawal-Notice-Memo-and-Questions

[7] Tom Lusch´s Website, see “May 7, 2012 update”

http://tomlusch.com/tomlusch/tomlusch/AAL77.html

9/11 Commission, Interview notes Charles Thomas, 04.05.04

http://tomlusch.com/tomlusch/tomlusch/AAL77_files/NARA to Lusch 20090820.pdf

[8] Email from Tom Lusch, 15.01.13, information based on NTAP flight data for AAL 77

[9] NTSB, Office of Research and Engineering, Flight path study – American Airlines Flight 77, February 19, 2002

http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB196/doc02.pdf

[10] Email from Miles Kara, 13.11.12, 9/11 Blogger, “Discussion with Miles Kara about 9/11 air defense,” 16.12.12

http://911blogger.com/news/2012-12-16/discussion-miles-kara-about-911-air-defense

[11] 9/11 Commission Report, p. 452, note 11

http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf

9/11 Commission, Team 7, Box 18, “American Airlines´ response to the February 3, 2004 requests by the 9/11 Commission C&F Ref: DTB/CRC/28079,” 15.03.04, Desmond T. Barry / Condon & Forsyth LLP, on behalf of American Airlines, p. 96

http://www.911myths.com/images/7/71/Team7_Box18_AAL-QFR-Responses.pdf