1 — "WE HAVE SOME PLANES"

Tuesday, September 11, 2001, dawned temperate and nearly cloudless in the eastern United States. Millions of men and women readied themselves for work. Some made their way to the Twin Towers, the signature structures of the World Trade Center complex in New York City. Others went to Arlington, Virginia, to the Pentagon. Across the Potomac River, the United States Congress was back in session. At the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, people began to line up for a White House tour. In Sarasota, Florida, President George W. Bush went for an early morning run.

For those heading to an airport, weather conditions could not have been better for a safe and pleasant journey. Among the travelers were Mohamed Atta and Abdul Aziz al Omari, who arrived at the airport in Portland, Maine.

1.1 INSIDE THE FOUR FLIGHTS

Boarding the Flights

Boston: American 11 and United 175. Atta and Omari boarded a 6:00 A.M. flight from Portland to Boston's Logan International Airport.1

When he checked in for his flight to Boston, Atta was selected by a computerized prescreening system known as CAPPS (Computer Assisted Passenger Prescreening System), created to identify passengers who should be subject to special security measures. Under security rules in place at the time, the only consequence of Atta's selection by CAPPS was that his checked bags were held off the plane until it was confirmed that he had boarded the aircraft. This did not hinder Atta's plans. 2

Atta and Omari arrived in Boston at 6:45. Seven minutes later, Atta apparently took a call from Marwan al Shehhi, a longtime colleague who was at another terminal at Logan Airport. They spoke for three minutes.3 It would be their final conversation.

Between 6:45 and 7:40, Atta and Omari, along with Satam al Suqami, Wail al Shehri, and Waleed al Shehri, checked in and boarded American Airlines Flight 11, bound for Los Angeles. The flight was scheduled to depart at 7:45.4

In another Logan terminal, Shehhi, joined by Fayez Banihammad, Mohand al Shehri, Ahmed al Ghamdi, and Hamza al Ghamdi, checked in for United Airlines Flight 175, also bound for Los Angeles. A couple of Shehhi's colleagues were obviously unused to travel; according to the United ticket agent, they had trouble understanding the standard security questions, and she had to go over them slowly until they gave the routine, reassuring answers.5 Their flight was scheduled to depart at 8:00.

The security checkpoints through which passengers, including Atta and his colleagues, gained access to the American 11 gate were operated by Globe Security under a contract with American Airlines. In a different terminal, the single checkpoint through which passengers for United 175 passed was controlled by United Airlines, which had contracted with Huntleigh USA to perform the screening.6

In passing through these checkpoints, each of the hijackers would have been screened by a walk-through metal detector calibrated to detect items with at least the metal content of a .22-caliber handgun. Anyone who might have set off that detector would have been screened with a hand wand-a procedure requiring the screener to identify the metal item or items that caused the alarm. In addition, an X-ray machine would have screened the hijackers' carry-on belongings. The screening was in place to identify and confiscate weapons and other items prohibited from being carried onto a commercial flight.7 None of the checkpoint supervisors recalled the hijackers or reported anything suspicious regarding their screening.8

While Atta had been selected by CAPPS in Portland, three members of his hijacking team-Suqami, Wail al Shehri, and Waleed al Shehri-were selected in Boston. Their selection affected only the handling of their checked bags, not their screening at the checkpoint. All five men cleared the checkpoint and made their way to the gate for American 11. Atta, Omari, and Suqami took their seats in business class (seats 8D, 8G, and 10B, respectively). The Shehri brothers had adjacent seats in row 2 (Wail in 2A,Waleed in 2B), in the first-class cabin. They boarded American 11 between 7:31 and 7:40. The aircraft pushed back from the gate at 7:40. 9

Shehhi and his team, none of whom had been selected by CAPPS, boarded United 175 between 7:23 and 7:28 (Banihammad in 2A, Shehri in 2B, Shehhi in 6C, Hamza al Ghamdi in 9C, and Ahmed al Ghamdi in 9D).Their aircraft pushed back from the gate just before 8:00.10

Washington Dulles: American 77. Hundreds of miles southwest of Boston, at Dulles International Airport in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C., five more men were preparing to take their early morning flight. At 7:15, a pair of them, Khalid al Mihdhar and Majed Moqed, checked in at the American Airlines ticket counter for Flight 77, bound for Los Angeles. Within the next 20 minutes, they would be followed by Hani Hanjour and two brothers, Nawaf al Hazmi and Salem al Hazmi.11

Hani Hanjour, Khalid al Mihdhar, and Majed Moqed were flagged by CAPPS. The Hazmi brothers were also selected for extra scrutiny by the air-line's customer service representative at the check-in counter. He did so because one of the brothers did not have photo identification nor could he understand English, and because the agent found both of the passengers to be suspicious. The only consequence of their selection was that their checked bags were held off the plane until it was confirmed that they had boarded the aircraft.12

All five hijackers passed through the Main Terminal's west security screening checkpoint; United Airlines, which was the responsible air carrier, had contracted out the work to Argenbright Security.13 The checkpoint featured closed-circuit television that recorded all passengers, including the hijackers, as they were screened. At 7:18, Mihdhar and Moqed entered the security checkpoint.

Mihdhar and Moqed placed their carry-on bags on the belt of the X-ray machine and proceeded through the first metal detector. Both set off the alarm, and they were directed to a second metal detector. Mihdhar did not trigger the alarm and was permitted through the checkpoint. After Moqed set it off, a screener wanded him. He passed this inspection.14

About 20 minutes later, at 7:35, another passenger for Flight 77, Hani Han-jour, placed two carry-on bags on the X-ray belt in the Main Terminal's west checkpoint, and proceeded, without alarm, through the metal detector. A short time later, Nawaf and Salem al Hazmi entered the same checkpoint. Salem al Hazmi cleared the metal detector and was permitted through; Nawaf al Hazmi set off the alarms for both the first and second metal detectors and was then hand-wanded before being passed. In addition, his over-the-shoulder carry-on bag was swiped by an explosive trace detector and then passed. The video footage indicates that he was carrying an unidentified item in his back pocket, clipped to its rim.15

When the local civil aviation security office of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) later investigated these security screening operations, the screeners recalled nothing out of the ordinary. They could not recall that any of the passengers they screened were CAPPS selectees. We asked a screening expert to review the videotape of the hand-wanding, and he found the quality of the screener's work to have been "marginal at best." The screener should have "resolved" what set off the alarm; and in the case of both Moqed and Hazmi, it was clear that he did not.16

At 7:50, Majed Moqed and Khalid al Mihdhar boarded the flight and were seated in 12A and 12B in coach. Hani Hanjour, assigned to seat 1B (first class), soon followed.The Hazmi brothers, sitting in 5E and 5F, joined Hanjour in the first-class cabin.17

Newark: United 93. Between 7:03 and 7:39, Saeed al Ghamdi, Ahmed al Nami, Ahmad al Haznawi, and Ziad Jarrah checked in at the United Airlines ticket counter for Flight 93, going to Los Angeles. Two checked bags; two did not. Haznawi was selected by CAPPS. His checked bag was screened for explosives and then loaded on the plane.18

The four men passed through the security checkpoint, owned by United Airlines and operated under contract by Argenbright Security. Like the checkpoints in Boston, it lacked closed-circuit television surveillance so there is no documentary evidence to indicate when the hijackers passed through the checkpoint, what alarms may have been triggered, or what security procedures were administered. The FAA interviewed the screeners later; none recalled anything unusual or suspicious.19

The four men boarded the plane between 7:39 and 7:48. All four had seats in the first-class cabin; their plane had no business-class section. Jarrah was in seat 1B, closest to the cockpit; Nami was in 3C, Ghamdi in 3D, and Haznawi in 6B.20

The 19 men were aboard four transcontinental flights.21 They were planning to hijack these planes and turn them into large guided missiles, loaded with up to 11,400 gallons of jet fuel. By 8:00 A.M. on the morning of Tuesday, September 11, 2001, they had defeated all the security layers that America's civil aviation security system then had in place to prevent a hijacking.

The Hijacking of American 11

American Airlines Flight 11 provided nonstop service from Boston to Los Angeles. On September 11, Captain John Ogonowski and First Officer Thomas McGuinness piloted the Boeing 767. It carried its full capacity of nine flight attendants. Eighty-one passengers boarded the flight with them (including the five terrorists).22

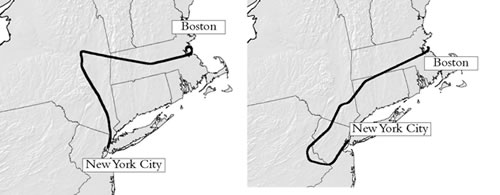

The plane took off at 7:59. Just before 8:14, it had climbed to 26,000 feet, not quite its initial assigned cruising altitude of 29,000 feet. All communications and flight profile data were normal. About this time the "Fasten Seatbelt" sign would usually have been turned off and the flight attendants would have begun preparing for cabin service.23

At that same time, American 11 had its last routine communication with the ground when it acknowledged navigational instructions from the FAA's air traffic control (ATC) center in Boston. Sixteen seconds after that transmis-sion, ATC instructed the aircraft's pilots to climb to 35,000 feet. That message and all subsequent attempts to contact the flight were not acknowledged. From this and other evidence, we believe the hijacking began at 8:14 or shortly thereafter.24

Reports from two flight attendants in the coach cabin, Betty Ong and Madeline "Amy" Sweeney, tell us most of what we know about how the hijacking happened. As it began, some of the hijackers-most likely Wail al Shehri and Waleed al Shehri, who were seated in row 2 in first class-stabbed the two unarmed flight attendants who would have been preparing for cabin service.25

We do not know exactly how the hijackers gained access to the cockpit; FAA rules required that the doors remain closed and locked during flight. Ong speculated that they had "jammed their way" in. Perhaps the terrorists stabbed the flight attendants to get a cockpit key, to force one of them to open the cockpit door, or to lure the captain or first officer out of the cockpit. Or the flight attendants may just have been in their way.26

At the same time or shortly thereafter, Atta-the only terrorist on board trained to fly a jet-would have moved to the cockpit from his business-class seat, possibly accompanied by Omari. As this was happening, passenger Daniel Lewin, who was seated in the row just behind Atta and Omari, was stabbed by one of the hijackers-probably Satam al Suqami, who was seated directly behind Lewin. Lewin had served four years as an officer in the Israeli military. He may have made an attempt to stop the hijackers in front of him, not realizing that another was sitting behind him.27

The hijackers quickly gained control and sprayed Mace, pepper spray, or some other irritant in the first-class cabin, in order to force the passengers and flight attendants toward the rear of the plane.They claimed they had a bomb.28

About five minutes after the hijacking began, Betty Ong contacted the American Airlines Southeastern Reservations Office in Cary, North Carolina, via an AT&T airphone to report an emergency aboard the flight. This was the first of several occasions on 9/11 when flight attendants took action outside the scope of their training, which emphasized that in a hijacking, they were to communicate with the cockpit crew. The emergency call lasted approximately 25 minutes, as Ong calmly and professionally relayed information about events taking place aboard the airplane to authorities on the ground.29

At 8:19, Ong reported: "The cockpit is not answering, somebody's stabbed in business class-and I think there's Mace-that we can't breathe-I don't know, I think we're getting hijacked." She then told of the stabbings of the two flight attendants.30

At 8:21, one of the American employees receiving Ong's call in North Carolina, Nydia Gonzalez, alerted the American Airlines operations center in Fort Worth, Texas, reaching Craig Marquis, the manager on duty. Marquis soon realized this was an emergency and instructed the airline's dispatcher responsible for the flight to contact the cockpit. At 8:23, the dispatcher tried unsuccessfully to contact the aircraft. Six minutes later, the air traffic control specialist in American's operations center contacted the FAA's Boston Air Traffic Control Center about the flight. The center was already aware of the problem.31

Boston Center knew of a problem on the flight in part because just before 8:25 the hijackers had attempted to communicate with the passengers. The microphone was keyed, and immediately one of the hijackers said, "Nobody move. Everything will be okay. If you try to make any moves, you'll endanger yourself and the airplane. Just stay quiet." Air traffic controllers heard the transmission; Ong did not. The hijackers probably did not know how to operate the cockpit radio communication system correctly, and thus inadvertently broadcast their message over the air traffic control channel instead of the cabin public-address channel. Also at 8:25, and again at 8:29, Amy Sweeney got through to the American Flight Services Office in Boston but was cut off after she reported someone was hurt aboard the flight. Three minutes later, Sweeney was reconnected to the office and began relaying updates to the manager, Michael Woodward.32

At 8:26, Ong reported that the plane was "flying erratically." A minute later, Flight 11 turned south. American also began getting identifications of the hijackers, as Ong and then Sweeney passed on some of the seat numbers of those who had gained unauthorized access to the cockpit.33

Sweeney calmly reported on her line that the plane had been hijacked; a man in first class had his throat slashed; two flight attendants had been stabbed-one was seriously hurt and was on oxygen while the other's wounds seemed minor; a doctor had been requested; the flight attendants were unable to contact the cockpit; and there was a bomb in the cockpit. Sweeney told Woodward that she and Ong were trying to relay as much information as they could to people on the ground.34

At 8:38, Ong told Gonzalez that the plane was flying erratically again. Around this time Sweeney told Woodward that the hijackers were Middle Easterners, naming three of their seat numbers. One spoke very little English and one spoke excellent English. The hijackers had gained entry to the cockpit, and she did not know how. The aircraft was in a rapid descent.35

At 8:41, Sweeney told Woodward that passengers in coach were under the impression that there was a routine medical emergency in first class. Other flight attendants were busy at duties such as getting medical supplies while Ong and Sweeney were reporting the events.36

At 8:41, in American's operations center, a colleague told Marquis that the air traffic controllers declared Flight 11 a hijacking and "think he's [American 11] headed toward Kennedy [airport in New York City].They're moving everybody out of the way. They seem to have him on a primary radar. They seem to think that he is descending."37

At 8:44, Gonzalez reported losing phone contact with Ong. About this same time Sweeney reported to Woodward," Something is wrong. We are in a rapid descent . . . we are all over the place." Woodward asked Sweeney to look out the window to see if she could determine where they were. Sweeney responded: "We are flying low. We are flying very, very low. We are flying way too low." Seconds later she said, "Oh my God we are way too low." The phone call ended.38

At 8:46:40, American 11 crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center in New York City.39 All on board, along with an unknown number of people in the tower, were killed instantly.

The Hijacking of United 175

United Airlines Flight 175 was scheduled to depart for Los Angeles at 8:00. Captain Victor Saracini and First Officer Michael Horrocks piloted the Boeing 767, which had seven flight attendants. Fifty-six passengers boarded the flight.40

United 175 pushed back from its gate at 7:58 and departed Logan Airport at 8:14. By 8:33, it had reached its assigned cruising altitude of 31,000 feet. The flight attendants would have begun their cabin service.41

The flight had taken off just as American 11 was being hijacked, and at 8:42 the United 175 flight crew completed their report on a "suspicious transmission" overheard from another plane (which turned out to have been Flight 11) just after takeoff. This was United 175's last communication with the ground.42

The hijackers attacked sometime between 8:42 and 8:46.They used knives (as reported by two passengers and a flight attendant), Mace (reported by one passenger), and the threat of a bomb (reported by the same passenger). They stabbed members of the flight crew (reported by a flight attendant and one passenger). Both pilots had been killed (reported by one flight attendant).The eyewitness accounts came from calls made from the rear of the plane, from passengers originally seated further forward in the cabin, a sign that passengers and perhaps crew had been moved to the back of the aircraft. Given similarities to American 11 in hijacker seating and in eyewitness reports of tactics and weapons, as well as the contact between the presumed team leaders, Atta and Shehhi, we believe the tactics were similar on both flights.43

The first operational evidence that something was abnormal on United 175 came at 8:47, when the aircraft changed beacon codes twice within a minute. At 8:51, the flight deviated from its assigned altitude, and a minute later New York air traffic controllers began repeatedly and unsuccessfully trying to contact it.44

At 8:52, in Easton, Connecticut, a man named Lee Hanson received a phone call from his son Peter, a passenger on United 175. His son told him: "I think they've taken over the cockpit-An attendant has been stabbed- and someone else up front may have been killed. The plane is making strange moves. Call United Airlines-Tell them it's Flight 175, Boston to LA." Lee Hanson then called the Easton Police Department and relayed what he had heard.45

Also at 8:52, a male flight attendant called a United office in San Francisco, reaching Marc Policastro. The flight attendant reported that the flight had been hijacked, both pilots had been killed, a flight attendant had been stabbed, and the hijackers were probably flying the plane. The call lasted about two minutes, after which Policastro and a colleague tried unsuccessfully to contact the flight.46

At 8:58, the flight took a heading toward New York City.47

At 8:59, Flight 175 passenger Brian David Sweeney tried to call his wife, Julie. He left a message on their home answering machine that the plane had been hijacked. He then called his mother, Louise Sweeney, told her the flight had been hijacked, and added that the passengers were thinking about storming the cockpit to take control of the plane away from the hijackers.48

At 9:00, Lee Hanson received a second call from his son Peter:

It's getting bad, Dad-A stewardess was stabbed-They seem to have knives and Mace-They said they have a bomb-It's getting very bad on the plane-Passengers are throwing up and getting sick-The plane is making jerky movements-I don't think the pilot is flying the plane-I think we are going down-I think they intend to go to Chicago or someplace and fly into a building-Don't worry, Dad- If it happens, it'll be very fast-My God, my God.49

The call ended abruptly. Lee Hanson had heard a woman scream just before it cut off. He turned on a television, and in her home so did Louise Sweeney. Both then saw the second aircraft hit the World Trade Center.50

At 9:03:11, United Airlines Flight 175 struck the South Tower of the World Trade Center.51 All on board, along with an unknown number of people in the tower, were killed instantly.

The Hijacking of American 77

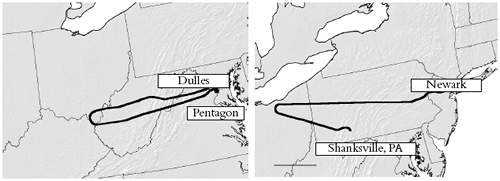

American Airlines Flight 77 was scheduled to depart from Washington Dulles for Los Angeles at 8:10. The aircraft was a Boeing 757 piloted by Captain Charles F. Burlingame and First Officer David Charlebois. There were four flight attendants. On September 11, the flight carried 58 passengers.52

American 77 pushed back from its gate at 8:09 and took off at 8:20. At 8:46, the flight reached its assigned cruising altitude of 35,000 feet. Cabin service would have begun. At 8:51, American 77 transmitted its last routine radio communication. The hijacking began between 8:51 and 8:54. As on American 11 and United 175, the hijackers used knives (reported by one passenger) and moved all the passengers (and possibly crew) to the rear of the aircraft (reported by one flight attendant and one passenger). Unlike the earlier flights, the Flight 77 hijackers were reported by a passenger to have box cutters. Finally, a passenger reported that an announcement had been made by the "pilot" that the plane had been hijacked. Neither of the firsthand accounts mentioned any stabbings or the threat or use of either a bomb or Mace, though both witnesses began the flight in the first-class cabin.53

At 8:54, the aircraft deviated from its assigned course, turning south. Two minutes later the transponder was turned off and even primary radar contact with the aircraft was lost. The Indianapolis Air Traffic Control Center repeatedly tried and failed to contact the aircraft. American Airlines dispatchers also tried, without success.54

At 9:00, American Airlines Executive Vice President Gerard Arpey learned that communications had been lost with American 77.This was now the second American aircraft in trouble. He ordered all American Airlines flights in the Northeast that had not taken off to remain on the ground. Shortly before 9:10, suspecting that American 77 had been hijacked, American headquarters concluded that the second aircraft to hit the World Trade Center might have been Flight 77. After learning that United Airlines was missing a plane, American Airlines headquarters extended the ground stop nationwide.55

At 9:12, Renee May called her mother, Nancy May, in Las Vegas. She said her flight was being hijacked by six individuals who had moved them to the rear of the plane. She asked her mother to alert American Airlines. Nancy May and her husband promptly did so.56

At some point between 9:16 and 9:26, Barbara Olson called her husband, Ted Olson, the solicitor general of the United States. She reported that the flight had been hijacked, and the hijackers had knives and box cutters. She further indicated that the hijackers were not aware of her phone call, and that they had put all the passengers in the back of the plane. About a minute into the conversation, the call was cut off. Solicitor General Olson tried unsuccessfully to reach Attorney General John Ashcroft.57

Shortly after the first call, Barbara Olson reached her husband again. She reported that the pilot had announced that the flight had been hijacked, and she asked her husband what she should tell the captain to do. Ted Olson asked for her location and she replied that the aircraft was then flying over houses. Another passenger told her they were traveling northeast. The Solicitor General then informed his wife of the two previous hijackings and crashes. She did not display signs of panic and did not indicate any awareness of an impending crash. At that point, the second call was cut off.58

At 9:29, the autopilot on American 77 was disengaged; the aircraft was at 7,000 feet and approximately 38 miles west of the Pentagon.59 At 9:32, controllers at the Dulles Terminal Radar Approach Control "observed a primary radar target tracking eastbound at a high rate of speed." This was later determined to have been Flight 77.

At 9:34, Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport advised the Secret Service of an unknown aircraft heading in the direction of the White House. American 77 was then 5 miles west-southwest of the Pentagon and began a 330-degree turn. At the end of the turn, it was descending through 2,200 feet, pointed toward the Pentagon and downtown Washington. The hijacker pilot then advanced the throttles to maximum power and dove toward the Pentagon.60

At 9:37:46, American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon, traveling at approximately 530 miles per hour.61 All on board, as well as many civilian and military personnel in the building, were killed.

The Battle for United 93

At 8:42, United Airlines Flight 93 took off from Newark (New Jersey) Liberty International Airport bound for San Francisco. The aircraft was piloted by Captain Jason Dahl and First Officer Leroy Homer, and there were five flight attendants. Thirty-seven passengers, including the hijackers, boarded the plane. Scheduled to depart the gate at 8:00, the Boeing 757's takeoff was delayed because of the airport's typically heavy morning traffic.62

The hijackers had planned to take flights scheduled to depart at 7:45 (American 11), 8:00 (United 175 and United 93), and 8:10 (American 77). Three of the flights had actually taken off within 10 to 15 minutes of their planned departure times. United 93 would ordinarily have taken off about 15 minutes after pulling away from the gate. When it left the ground at 8:42, the flight was running more than 25 minutes late.63

As United 93 left Newark, the flight's crew members were unaware of the hijacking of American 11.Around 9:00, the FAA, American, and United were facing the staggering realization of apparent multiple hijackings. At 9:03, they would see another aircraft strike the World Trade Center. Crisis managers at the FAA and the airlines did not yet act to warn other aircraft.64 At the same time, Boston Center realized that a message transmitted just before 8:25 by the hijacker pilot of American 11 included the phrase, "We have some planes."65

No one at the FAA or the airlines that day had ever dealt with multiple hijackings. Such a plot had not been carried out anywhere in the world in more than 30 years, and never in the United States. As news of the hijackings filtered through the FAA and the airlines, it does not seem to have occurred to their leadership that they needed to alert other aircraft in the air that they too might be at risk.66

United 175 was hijacked between 8:42 and 8:46, and awareness of that hijacking began to spread after 8:51. American 77 was hijacked between 8:51 and 8:54. By 9:00, FAA and airline officials began to comprehend that attackers were going after multiple aircraft. American Airlines' nationwide ground stop between 9:05 and 9:10 was followed by a United Airlines ground stop. FAA controllers at Boston Center, which had tracked the first two hijackings, requested at 9:07 that Herndon Command Center "get messages to airborne aircraft to increase security for the cockpit." There is no evidence that Herndon took such action. Boston Center immediately began speculating about other aircraft that might be in danger, leading them to worry about a transcontinental flight-Delta 1989-that in fact was not hijacked. At 9:19, the FAA's New England regional office called Herndon and asked that Cleveland Center advise Delta 1989 to use extra cockpit security.67

Several FAA air traffic control officials told us it was the air carriers' responsibility to notify their planes of security problems. One senior FAA air traffic control manager said that it was simply not the FAA's place to order the airlines what to tell their pilots.68 We believe such statements do not reflect an adequate appreciation of the FAA's responsibility for the safety and security of civil aviation.

The airlines bore responsibility, too. They were facing an escalating number of conflicting and, for the most part, erroneous reports about other flights, as well as a continuing lack of vital information from the FAA about the hijacked flights. We found no evidence, however, that American Airlines sent any cockpit warnings to its aircraft on 9/11. United's first decisive action to notify its airborne aircraft to take defensive action did not come until 9:19, when a United flight dispatcher, Ed Ballinger, took the initiative to begin transmitting warnings to his 16 transcontinental flights: "Beware any cockpit intrusion- Two a/c [aircraft] hit World Trade Center." One of the flights that received the warning was United 93. Because Ballinger was still responsible for his other flights as well as Flight 175, his warning message was not transmitted to Flight 93 until 9:23.69

By all accounts, the first 46 minutes of Flight 93's cross-country trip proceeded routinely. Radio communications from the plane were normal. Heading, speed, and altitude ran according to plan. At 9:24, Ballinger's warning to United 93 was received in the cockpit. Within two minutes, at 9:26, the pilot, Jason Dahl, responded with a note of puzzlement: "Ed, confirm latest mssg plz-Jason."70

The hijackers attacked at 9:28. While traveling 35,000 feet above eastern Ohio, United 93 suddenly dropped 700 feet. Eleven seconds into the descent, the FAA's air traffic control center in Cleveland received the first of two radio transmissions from the aircraft. During the first broadcast, the captain or first officer could be heard declaring "Mayday" amid the sounds of a physical struggle in the cockpit. The second radio transmission, 35 seconds later, indicated that the fight was continuing. The captain or first officer could be heard shouting:" Hey get out of here-get out of here-get out of here."71

On the morning of 9/11, there were only 37 passengers on United 93-33 in addition to the 4 hijackers. This was below the norm for Tuesday mornings during the summer of 2001. But there is no evidence that the hijackers manipulated passenger levels or purchased additional seats to facilitate their operation.72

The terrorists who hijacked three other commercial flights on 9/11 operated in five-man teams. They initiated their cockpit takeover within 30 minutes of takeoff. On Flight 93, however, the takeover took place 46 minutes after takeoff and there were only four hijackers. The operative likely intended to round out the team for this flight, Mohamed al Kahtani, had been refused entry by a suspicious immigration inspector at Florida's Orlando International Airport in August.73

Because several passengers on United 93 described three hijackers on the plane, not four, some have wondered whether one of the hijackers had been able to use the cockpit jump seat from the outset of the flight. FAA rules allow use of this seat by documented and approved individuals, usually air carrier or FAA personnel. We have found no evidence indicating that one of the hijackers, or anyone else, sat there on this flight. All the hijackers had assigned seats in first class, and they seem to have used them. We believe it is more likely that Jarrah, the crucial pilot-trained member of their team, remained seated and inconspicuous until after the cockpit was seized; and once inside, he would not have been visible to the passengers.74

At 9:32, a hijacker, probably Jarrah, made or attempted to make the following announcement to the passengers of Flight 93:"Ladies and Gentlemen: Here the captain, please sit down keep remaining sitting. We have a bomb on board. So, sit." The flight data recorder (also recovered) indicates that Jarrah then instructed the plane's autopilot to turn the aircraft around and head east.75

The cockpit voice recorder data indicate that a woman, most likely a flight attendant, was being held captive in the cockpit. She struggled with one of the hijackers who killed or otherwise silenced her.76

Shortly thereafter, the passengers and flight crew began a series of calls from GTE airphones and cellular phones. These calls between family, friends, and colleagues took place until the end of the flight and provided those on the ground with firsthand accounts. They enabled the passengers to gain critical information, including the news that two aircraft had slammed into the World Trade Center.77

At 9:39, the FAA's Cleveland Air Route Traffic Control Center overheard a second announcement indicating that there was a bomb on board, that the plane was returning to the airport, and that they should remain seated.78 While it apparently was not heard by the passengers, this announcement, like those on Flight 11 and Flight 77, was intended to deceive them. Jarrah, like Atta earlier, may have inadvertently broadcast the message because he did not know how to operate the radio and the intercom. To our knowledge none of them had ever flown an actual airliner before.

At least two callers from the flight reported that the hijackers knew that passengers were making calls but did not seem to care. It is quite possible Jarrah knew of the success of the assault on the World Trade Center. He could have learned of this from messages being sent by United Airlines to the cockpits of its transcontinental flights, including Flight 93, warning of cockpit intrusion and telling of the New York attacks. But even without them, he would certainly have understood that the attacks on the World Trade Center would already have unfolded, given Flight 93's tardy departure from Newark. If Jarrah did know that the passengers were making calls, it might not have occurred to him that they were certain to learn what had happened in New York, thereby defeating his attempts at deception.79

At least ten passengers and two crew members shared vital information with family, friends, colleagues, or others on the ground. All understood the plane had been hijacked. They said the hijackers wielded knives and claimed to have a bomb. The hijackers were wearing red bandanas, and they forced the passengers to the back of the aircraft.80

Callers reported that a passenger had been stabbed and that two people were lying on the floor of the cabin, injured or dead-possibly the captain and first officer. One caller reported that a flight attendant had been killed.81

One of the callers from United 93 also reported that he thought the hijackers might possess a gun. But none of the other callers reported the presence of a firearm. One recipient of a call from the aircraft recounted specifically asking her caller whether the hijackers had guns. The passenger replied that he did not see one. No evidence of firearms or of their identifiable remains was found at the aircraft's crash site, and the cockpit voice recorder gives no indication of a gun being fired or mentioned at any time. We believe that if the hijackers had possessed a gun, they would have used it in the flight's last minutes as the passengers fought back.82

Passengers on three flights reported the hijackers' claim of having a bomb. The FBI told us they found no trace of explosives at the crash sites. One of the passengers who mentioned a bomb expressed his belief that it was not real. Lacking any evidence that the hijackers attempted to smuggle such illegal items past the security screening checkpoints, we believe the bombs were probably fake.83

During at least five of the passengers' phone calls, information was shared about the attacks that had occurred earlier that morning at the World Trade Center. Five calls described the intent of passengers and surviving crew members to revolt against the hijackers. According to one call, they voted on whether to rush the terrorists in an attempt to retake the plane. They decided, and acted.84

At 9:57, the passenger assault began. Several passengers had terminated phone calls with loved ones in order to join the revolt. One of the callers ended her message as follows: "Everyone's running up to first class. I've got to go. Bye."85

The cockpit voice recorder captured the sounds of the passenger assault muffled by the intervening cockpit door. Some family members who listened to the recording report that they can hear the voice of a loved one among the din. We cannot identify whose voices can be heard. But the assault was sustained.86

In response, Jarrah immediately began to roll the airplane to the left and right, attempting to knock the passengers off balance. At 9:58:57, Jarrah told another hijacker in the cockpit to block the door. Jarrah continued to roll the airplane sharply left and right, but the assault continued. At 9:59:52, Jarrah changed tactics and pitched the nose of the airplane up and down to disrupt the assault. The recorder captured the sounds of loud thumps, crashes, shouts, and breaking glasses and plates. At 10:00:03, Jarrah stabilized the airplane.87

Five seconds later, Jarrah asked, "Is that it? Shall we finish it off?" A hijacker responded, "No. Not yet. When they all come, we finish it off." The sounds of fighting continued outside the cockpit. Again, Jarrah pitched the nose of the aircraft up and down. At 10:00:26, a passenger in the background said, "In the cockpit. If we don't we'll die!" Sixteen seconds later, a passenger yelled, "Roll it!" Jarrah stopped the violent maneuvers at about 10:01:00 and said, "Allah is the greatest! Allah is the greatest!" He then asked another hijacker in the cock-pit, "Is that it? I mean, shall we put it down?" to which the other replied, "Yes, put it in it, and pull it down."88

The passengers continued their assault and at 10:02:23, a hijacker said, "Pull it down! Pull it down!" The hijackers remained at the controls but must have judged that the passengers were only seconds from overcoming them. The airplane headed down; the control wheel was turned hard to the right. The airplane rolled onto its back, and one of the hijackers began shouting "Allah is the greatest. Allah is the greatest." With the sounds of the passenger counterattack continuing, the aircraft plowed into an empty field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, at 580 miles per hour, about 20 minutes' flying time from Washington, D.C.89

Jarrah's objective was to crash his airliner into symbols of the American Republic, the Capitol or the White House. He was defeated by the alerted, unarmed passengers of United 93.

1.2 IMPROVISING A HOMELAND DEFENSE

The FAA and NORAD

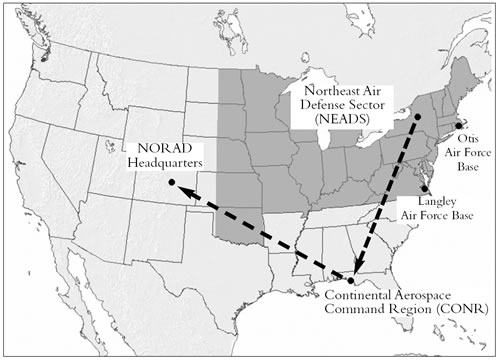

On 9/11, the defense of U.S. airspace depended on close interaction between two federal agencies: the FAA and the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD).The most recent hijacking that involved U.S. air traffic controllers, FAA management, and military coordination had occurred in 1993.90 In order to understand how the two agencies interacted eight years later, we will review their missions, command and control structures, and working relationship on the morning of 9/11.

FAA Mission and Structure. As of September 11, 2001, the FAA was mandated by law to regulate the safety and security of civil aviation. From an air traffic controller's perspective, that meant maintaining a safe distance between airborne aircraft.91

Many controllers work at the FAA's 22 Air Route Traffic Control Centers. They are grouped under regional offices and coordinate closely with the national Air Traffic Control System Command Center, located in Herndon,

FAA Air Traffic Control Centers

Reporting structure, Northeast Air Defense Sector

Graphics courtesy of ESRI

Virginia, which oversees daily traffic flow within the entire airspace system. FAA headquarters is ultimately responsible for the management of the National Airspace System. The Operations Center located at FAA headquarters receives notifications of incidents, including accidents and hijackings.92

FAA Control Centers often receive information and make operational decisions independently of one another. On 9/11, the four hijacked aircraft were monitored mainly by the centers in Boston, New York, Cleveland, and Indianapolis. Each center thus had part of the knowledge of what was going on across the system. What Boston knew was not necessarily known by centers in New York, Cleveland, or Indianapolis, or for that matter by the Command Center in Herndon or by FAA headquarters in Washington.

Controllers track airliners such as the four aircraft hijacked on 9/11 primarily by watching the data from a signal emitted by each aircraft's transponder equipment. Those four planes, like all aircraft traveling above 10,000 feet, were required to emit a unique transponder signal while in flight.93

On 9/11, the terrorists turned off the transponders on three of the four hijacked aircraft. With its transponder off, it is possible, though more difficult, to track an aircraft by its primary radar returns. But unlike transponder data, primary radar returns do not show the aircraft's identity and altitude. Controllers at centers rely so heavily on transponder signals that they usually do not display primary radar returns on their radar scopes. But they can change the configuration of their scopes so they can see primary radar returns. They did this on 9/11 when the transponder signals for three of the aircraft disappeared.94

Before 9/11, it was not unheard of for a commercial aircraft to deviate slightly from its course, or for an FAA controller to lose radio contact with a pilot for a short period of time. A controller could also briefly lose a commercial aircraft's transponder signal, although this happened much less frequently. However, the simultaneous loss of radio and transponder signal would be a rare and alarming occurrence, and would normally indicate a catastrophic system failure or an aircraft crash. In all of these instances, the job of the controller was to reach out to the aircraft, the parent company of the aircraft, and other planes in the vicinity in an attempt to reestablish communications and set the aircraft back on course. Alarm bells would not start ringing until these efforts-which could take five minutes or more-were tried and had failed.95

NORAD Mission and Structure. NORAD is a binational command established in 1958 between the United States and Canada. Its mission was, and is, to defend the airspace of North America and protect the continent. That mission does not distinguish between internal and external threats; but because NORAD was created to counter the Soviet threat, it came to define its job as defending against external attacks.96

The threat of Soviet bombers diminished significantly as the Cold War ended, and the number of NORAD alert sites was reduced from its Cold War high of 26. Some within the Pentagon argued in the 1990s that the alert sites should be eliminated entirely. In an effort to preserve their mission, members of the air defense community advocated the importance of air sovereignty against emerging "asymmetric threats" to the United States: drug smuggling, "non-state and state-sponsored terrorists," and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and ballistic missile technology.97

NORAD perceived the dominant threat to be from cruise missiles. Other threats were identified during the late 1990s, including terrorists' use of aircraft as weapons. Exercises were conducted to counter this threat, but they were not based on actual intelligence. In most instances, the main concern was the use of such aircraft to deliver weapons of mass destruction.

Prior to 9/11, it was understood that an order to shoot down a commercial aircraft would have to be issued by the National Command Authority (a phrase used to describe the president and secretary of defense). Exercise planners also assumed that the aircraft would originate from outside the United States, allowing time to identify the target and scramble interceptors. The threat of terrorists hijacking commercial airliners within the United States-and using them as guided missiles-was not recognized by NORAD before 9/11.98

Notwithstanding the identification of these emerging threats, by 9/11 there were only seven alert sites left in the United States, each with two fighter aircraft on alert. This led some NORAD commanders to worry that NORAD was not postured adequately to protect the United States.99

In the United States, NORAD is divided into three sectors. On 9/11, all the hijacked aircraft were in NORAD's Northeast Air Defense Sector (also known as NEADS), which is based in Rome, New York. That morning NEADS could call on two alert sites, each with one pair of ready fighters: Otis Air National Guard Base in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and Langley Air Force Base in Hampton, Virginia.100 Other facilities, not on "alert," would need time to arm the fighters and organize crews.

NEADS reported to the Continental U.S. NORAD Region (CONR) headquarters, in Panama City, Florida, which in turn reported to NORAD headquarters, in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Interagency Collaboration. The FAA and NORAD had developed protocols for working together in the event of a hijacking. As they existed on 9/11, the protocols for the FAA to obtain military assistance from NORAD required multiple levels of notification and approval at the highest levels of government.101

FAA guidance to controllers on hijack procedures assumed that the aircraft pilot would notify the controller via radio or by "squawking" a transponder code of "7500"-the universal code for a hijack in progress. Controllers would notify their supervisors, who in turn would inform management all the way up to FAA headquarters in Washington. Headquarters had a hijack coordinator, who was the director of the FAA Office of Civil Aviation Security or his or her designate.102

If a hijack was confirmed, procedures called for the hijack coordinator on duty to contact the Pentagon's National Military Command Center (NMCC) and to ask for a military escort aircraft to follow the flight, report anything unusual, and aid search and rescue in the event of an emergency. The NMCC would then seek approval from the Office of the Secretary of Defense to provide military assistance. If approval was given, the orders would be transmitted down NORAD's chain of command.103

The NMCC would keep the FAA hijack coordinator up to date and help the FAA centers coordinate directly with the military. NORAD would receive tracking information for the hijacked aircraft either from joint use radar or from the relevant FAA air traffic control facility. Every attempt would be made to have the hijacked aircraft squawk 7500 to help NORAD track it.104

The protocols did not contemplate an intercept. They assumed the fighter escort would be discreet, "vectored to a position five miles directly behind the hijacked aircraft," where it could perform its mission to monitor the aircraft's flight path.105

In sum, the protocols in place on 9/11 for the FAA and NORAD to respond to a hijacking presumed that

- the hijacked aircraft would be readily identifiable and would not attempt to disappear;

- there would be time to address the problem through the appropriate FAA and NORAD chains of command; and

- hijacking would take the traditional form: that is, it would not be a suicide hijacking designed to convert the aircraft into a guided missile.

On the morning of 9/11, the existing protocol was unsuited in every respect for what was about to happen.

American Airlines Flight 11 FAA Awareness. Although the Boston Center air traffic controller realized at an early stage that there was something wrong with American 11, he did not immediately interpret the plane's failure to respond as a sign that it had been hijacked. At 8:14, when the flight failed to heed his instruction to climb to 35,000 feet, the controller repeatedly tried to raise the flight. He reached out to the pilot on the emergency frequency. Though there was no response, he kept trying to contact the aircraft.106

At 8:21, American 11 turned off its transponder, immediately degrading the information available about the aircraft. The controller told his supervisor that he thought something was seriously wrong with the plane, although neither suspected a hijacking. The supervisor instructed the controller to follow standard procedures for handling a "no radio" aircraft.107

The controller checked to see if American Airlines could establish communication with American 11. He became even more concerned as its route changed, moving into another sector's airspace. Controllers immediately began to move aircraft out of its path, and asked other aircraft in the vicinity to look for American 11.108

At 8:24:38, the following transmission came from American 11:

American 11: We have some planes. Just stay quiet, and you'll be okay. We are returning to the airport.

The controller only heard something unintelligible; he did not hear the specific words "we have some planes." The next transmission came seconds later:

American 11: Nobody move. Everything will be okay. If you try to make any moves, you'll endanger yourself and the airplane. Just stay quiet.109

The controller told us that he then knew it was a hijacking. He alerted his supervisor, who assigned another controller to assist him. He redoubled his efforts to ascertain the flight's altitude. Because the controller didn't understand the initial transmission, the manager of Boston Center instructed his quality assurance specialist to "pull the tape" of the radio transmission, listen to it closely, and report back.110

Between 8:25 and 8:32, in accordance with the FAA protocol, Boston Center managers started notifying their chain of command that American 11 had been hijacked. At 8:28, Boston Center called the Command Center in Herndon to advise that it believed American 11 had been hijacked and was heading toward New York Center's airspace.

By this time, American 11 had taken a dramatic turn to the south. At 8:32, the Command Center passed word of a possible hijacking to the Operations Center at FAA headquarters. The duty officer replied that security personnel at headquarters had just begun discussing the apparent hijack on a conference call with the New England regional office. FAA headquarters began to follow the hijack protocol but did not contact the NMCC to request a fighter escort.111

The Herndon Command Center immediately established a teleconference between Boston, New York, and Cleveland Centers so that Boston Center could help the others understand what was happening.112

At 8:34, the Boston Center controller received a third transmission from American 11:

American 11: Nobody move please. We are going back to the airport. Don't try to make any stupid moves.113

In the succeeding minutes, controllers were attempting to ascertain the altitude of the southbound flight.114

Military Notification and Response. Boston Center did not follow the protocol in seeking military assistance through the prescribed chain of command. In addition to notifications within the FAA, Boston Center took the initiative, at 8:34, to contact the military through the FAA's Cape Cod facility. The center also tried to contact a former alert site in Atlantic City, unaware it had been phased out. At 8:37:52, Boston Center reached NEADS. This was the first notification received by the military-at any level-that American 11 had been hijacked:115

FAA: Hi. Boston Center TMU [Traffic Management Unit], we have a problem here. We have a hijacked aircraft headed towards New York, and we need you guys to, we need someone to scramble some F-16s or something up there, help us out.NEADS: Is this real-world or exercise?

FAA: No, this is not an exercise, not a test.116

NEADS ordered to battle stations the two F-15 alert aircraft at Otis Air Force Base in Falmouth, Massachusetts, 153 miles away from New York City. The air defense of America began with this call.117

At NEADS, the report of the hijacking was relayed immediately to Battle Commander Colonel Robert Marr. After ordering the Otis fighters to battle stations, Colonel Marr phoned Major General Larry Arnold, commanding general of the First Air Force and NORAD's Continental Region. Marr sought authorization to scramble the Otis fighters. General Arnold later recalled instructing Marr to "go ahead and scramble them, and we'll get authorities later." General Arnold then called NORAD headquarters to report.118

F-15 fighters were scrambled at 8:46 from Otis Air Force Base. But NEADS did not know where to send the alert fighter aircraft, and the officer directing the fighters pressed for more information: "I don't know where I'm scrambling these guys to. I need a direction, a destination." Because the hijackers had turned off the plane's transponder, NEADS personnel spent the next minutes searching their radar scopes for the primary radar return. American 11 struck the North Tower at 8:46. Shortly after 8:50, while NEADS personnel were still trying to locate the flight, word reached them that a plane had hit the World Trade Center.119

Radar data show the Otis fighters were airborne at 8:53. Lacking a target, they were vectored toward military-controlled airspace off the Long Island coast. To avoid New York area air traffic and uncertain about what to do, the fighters were brought down to military airspace to "hold as needed. "From 9:09 to 9:13, the Otis fighters stayed in this holding pattern.120

In summary, NEADS received notice of the hijacking nine minutes before it struck the North Tower. That nine minutes' notice before impact was the most the military would receive of any of the four hijackings.121

United Airlines Flight 175 FAA Awareness. One of the last transmissions from United Airlines Flight 175 is, in retrospect, chilling. By 8:40, controllers at the FAA's New York Center were seeking information on American 11. At approximately 8:42, shortly after entering New York Center's airspace, the pilot of United 175 broke in with the following transmission:

UAL 175: New York UAL 175 heavy.FAA: UAL 175 go ahead.

UAL 175:Yeah.We figured we'd wait to go to your center.Ah, we hearda suspicious transmission on our departure out of Boston, ah, with someone, ah, it sounded like someone keyed the mikes and said ah everyone ah stay in your seats.

FAA: Oh, okay. I'll pass that along over here.122

Minutes later, United 175 turned southwest without clearance from air traffic control. At 8:47, seconds after the impact of American 11, United 175's transponder code changed, and then changed again. These changes were not noticed for several minutes, however, because the same New York Center controller was assigned to both American 11 and United 175.The controller knew American 11 was hijacked; he was focused on searching for it after the aircraft disappeared at 8:46.123

At 8:48, while the controller was still trying to locate American 11, a New York Center manager provided the following report on a Command Center teleconference about American 11:

Manager, New York Center: Okay. This is New York Center. We're watching the airplane. I also had conversation with American Airlines, and they've told us that they believe that one of their stewardesses was stabbed and that there are people in the cockpit that have control of the aircraft, and that's all the information they have right now.124

The New York Center controller and manager were unaware that American 11 had already crashed.

At 8:51, the controller noticed the transponder change from United 175 and tried to contact the aircraft. There was no response. Beginning at 8:52, the controller made repeated attempts to reach the crew of United 175. Still no response. The controller checked his radio equipment and contacted another controller at 8:53, saying that "we may have a hijack" and that he could not find the aircraft.125

Another commercial aircraft in the vicinity then radioed in with "reports over the radio of a commuter plane hitting the World Trade Center." The controller spent the next several minutes handing off the other flights on his scope to other controllers and moving aircraft out of the way of the unidentified aircraft (believed to be United 175) as it moved southwest and then turned northeast toward New York City.126

At about 8:55, the controller in charge notified a New York Center manager that she believed United 175 had also been hijacked. The manager tried to notify the regional managers and was told that they were discussing a hijacked aircraft (presumably American 11) and refused to be disturbed. At 8:58, the New York Center controller searching for United 175 told another New York controller "we might have a hijack over here, two of them."127

Between 9:01 and 9:02, a manager from New York Center told the Command Center in Herndon:

Manager, New York Center: We have several situations going on here. It's escalating big, big time. We need to get the military involved with us.. . . We're, we're involved with something else, we have other aircraft that may have a similar situation going on here.128

The "other aircraft" referred to by New York Center was United 175. Evidence indicates that this conversation was the only notice received by either FAA headquarters or the Herndon Command Center prior to the second crash that there had been a second hijacking.

While the Command Center was told about this "other aircraft" at 9:01, New York Center contacted New York terminal approach control and asked for help in locating United 175.

Terminal: I got somebody who keeps coasting but it looks like he's going into one of the small airports down there.Center: Hold on a second. I'm trying to bring him up here and get you-There he is right there. Hold on.

Terminal: Got him just out of 9,500-9,000 now.

Center: Do you know who he is?

Terminal: We're just, we just we don't know who he is.We're just picking him up now.

Center (at 9:02): Alright. Heads up man, it looks like another one coming in.129

The controllers observed the plane in a rapid descent; the radar data terminated over Lower Manhattan. At 9:03, United 175 crashed into the South Tower.130

Meanwhile, a manager from Boston Center reported that they had deciphered what they had heard in one of the first hijacker transmissions from American 11:

Boston Center: Hey . . . you still there?New England Region:Yes, I am.

Boston Center: . . . as far as the tape, Bobby seemed to think the guy said that "we have planes." Now, I don't know if it was because it was the accent, or if there's more than one, but I'm gonna, I'm gonna reconfirm that for you, and I'll get back to you real quick. Okay?

New England Region: Appreciate it.

Unidentified Female Voice: They have what?

Boston Center: Planes, as in plural.

Boston Center: It sounds like, we're talking to New York, that there's another one aimed at the World Trade Center.

New England Region: There's another aircraft?

Boston Center: A second one just hit the Trade Center.

New England Region: Okay. Yeah, we gotta get-we gotta alert the military real quick on this.131

Boston Center immediately advised the New England Region that it was going to stop all departures at airports under its control. At 9:05, Boston Center confirmed for both the FAA Command Center and the New England Region that the hijackers aboard American 11 said "we have planes." At the same time, NewYork Center declared "ATC zero"-meaning that aircraft were not permitted to depart from, arrive at, or travel through New York Center's airspace until further notice.132

Within minutes of the second impact, Boston Center instructed its controllers to inform all aircraft in its airspace of the events in New York and to advise aircraft to heighten cockpit security. Boston Center asked the Herndon Command Center to issue a similar cockpit security alert nationwide. We have found no evidence to suggest that the Command Center acted on this request or issued any type of cockpit security alert.133

Military Notification and Response. The first indication that the NORAD air defenders had of the second hijacked aircraft, United 175, came in a phone call from New York Center to NEADS at 9:03.The notice came at about the time the plane was hitting the South Tower.134

By 9:08, the mission crew commander at NEADS learned of the second explosion at the World Trade Center and decided against holding the fighters in military airspace away from Manhattan:

Mission Crew Commander, NEADS: This is what I foresee that we probably need to do. We need to talk to FAA. We need to tell 'em if this stuff is gonna keep on going, we need to take those fighters, put 'em over Manhattan. That's best thing, that's the best play right now. So coordinate with the FAA. Tell 'em if there's more out there, which we don't know, let's get 'em over Manhattan. At least we got some kind of play.135

The FAA cleared the airspace. Radar data show that at 9:13, when the Otis fighters were about 115 miles away from the city, the fighters exited their holding pattern and set a course direct for Manhattan. They arrived at 9:25 and established a combat air patrol (CAP) over the city.136

Because the Otis fighters had expended a great deal of fuel in flying first to military airspace and then to New York, the battle commanders were concerned about refueling. NEADS considered scrambling alert fighters from Langley Air Force Base in Virginia to New York, to provide backup. The Langley fighters were placed on battle stations at 9:09.137 NORAD had no indication that any other plane had been hijacked.

American Airlines Flight 77

FAA Awareness. American 77 began deviating from

its flight plan at 8:54, with a slight turn toward the south. Two minutes later, it disappeared completely from radar at Indianapolis Center, which was controlling the flight.138

The controller tracking American 77 told us he noticed the aircraft turning to the southwest, and then saw the data disappear. The controller looked for primary radar returns. He searched along the plane's projected flight path and the airspace to the southwest where it had started to turn. No primary targets appeared. He tried the radios, first calling the aircraft directly, then the air-line. Again there was nothing. At this point, the Indianapolis controller had no knowledge of the situation in New York. He did not know that other aircraft had been hijacked. He believed American 77 had experienced serious electrical or mechanical failure, or both, and was gone.139

Shortly after 9:00, Indianapolis Center started notifying other agencies that American 77 was missing and had possibly crashed. At 9:08, Indianapolis Center asked Air Force Search and Rescue at Langley Air Force Base to look for a downed aircraft. The center also contacted the West Virginia State Police and asked whether any reports of a downed aircraft had been received. At 9:09, it reported the loss of contact to the FAA regional center, which passed this information to FAA headquarters at 9:24.140

By 9:20, Indianapolis Center learned that there were other hijacked aircraft, and began to doubt its initial assumption that American 77 had crashed. A discussion of this concern between the manager at Indianapolis and the Command Center in Herndon prompted it to notify some FAA field facilities that American 77 was lost. By 9:21, the Command Center, some FAA field facilities, and American Airlines had started to search for American 77.They feared it had been hijacked. At 9:25, the Command Center advised FAA headquarters of the situation.141

The failure to find a primary radar return for American 77 led us to investigate this issue further. Radar reconstructions performed after 9/11 reveal that FAA radar equipment tracked the flight from the moment its transponder was turned off at 8:56. But for 8 minutes and 13 seconds, between 8:56 and 9:05, this primary radar information on American 77 was not displayed to controllers at Indianapolis Center.142 The reasons are technical, arising from the way the software processed radar information, as well as from poor primary radar coverage where American 77 was flying.

According to the radar reconstruction, American 77 reemerged as a primary target on Indianapolis Center radar scopes at 9:05, east of its last known posi-tion. The target remained in Indianapolis Center's airspace for another six minutes, then crossed into the western portion of Washington Center's airspace at 9:10.As Indianapolis Center continued searching for the aircraft, two managers and the controller responsible for American 77 looked to the west and southwest along the flight's projected path, not east-where the aircraft was now heading. Managers did not instruct other controllers at Indianapolis Center to turn on their primary radar coverage to join in the search for American 77.143

In sum, Indianapolis Center never saw Flight 77 turn around. By the time it reappeared in primary radar coverage, controllers had either stopped looking for the aircraft because they thought it had crashed or were looking toward the west. Although the Command Center learned Flight 77 was missing, neither it nor FAA headquarters issued an all points bulletin to surrounding centers to search for primary radar targets. American 77 traveled undetected for 36 minutes on a course heading due east for Washington, D.C.144

By 9:25, FAA's Herndon Command Center and FAA headquarters knew two aircraft had crashed into the World Trade Center. They knew American 77 was lost. At least some FAA officials in Boston Center and the New England Region knew that a hijacker on board American 11 had said "we have some planes." Concerns over the safety of other aircraft began to mount. A manager at the Herndon Command Center asked FAA headquarters if they wanted to order a "nationwide ground stop." While this was being discussed by executives at FAA headquarters, the Command Center ordered one at 9:25.145

The Command Center kept looking for American 77. At 9:21, it advised the Dulles terminal control facility, and Dulles urged its controllers to look for primary targets. At 9:32, they found one. Several of the Dulles controllers "observed a primary radar target tracking eastbound at a high rate of speed" and notified Reagan National Airport. FAA personnel at both Reagan National and Dulles airports notified the Secret Service. The aircraft's identity or type was unknown.146

Reagan National controllers then vectored an unarmed National Guard C130H cargo aircraft, which had just taken off en route to Minnesota, to identify and follow the suspicious aircraft. The C-130H pilot spotted it, identified it as a Boeing 757, attempted to follow its path, and at 9:38, seconds after impact, reported to the control tower: "looks like that aircraft crashed into the Pentagon sir."147

Military Notification and Response. NORAD heard nothing about the search for American 77. Instead, the NEADS air defenders heard renewed reports about a plane that no longer existed: American 11.

At 9:21, NEADS received a report from the FAA:

FAA: Military, Boston Center. I just had a report that American 11 is still in the air, and it's on its way towards-heading towards Washington.NEADS: Okay. American 11 is still in the air?

FAA: Yes.

NEADS: On its way towards Washington?

FAA: That was another-it was evidently another aircraft that hit the tower. That's the latest report we have.

NEADS: Okay.

FAA: I'm going to try to confirm an ID for you, but I would assume he's somewhere over, uh, either New Jersey or somewhere further south.

NEADS: Okay. So American 11 isn't the hijack at all then, right?

FAA: No, he is a hijack.

NEADS: He-American 11 is a hijack?

FAA: Yes.

NEADS: And he's heading into Washington?

FAA: Yes. This could be a third aircraft.148

The mention of a "third aircraft" was not a reference to American 77.There was confusion at that moment in the FAA. Two planes had struck the World Trade Center, and Boston Center had heard from FAA headquarters in Washington that American 11 was still airborne. We have been unable to identify the source of this mistaken FAA information.

The NEADS technician who took this call from the FAA immediately passed the word to the mission crew commander, who reported to the NEADS battle commander:

Mission Crew Commander, NEADS: Okay, uh, American Airlines is still airborne. Eleven, the first guy, he's heading towards Washington. Okay? I think we need to scramble Langley right now. And I'm gonna take the fighters from Otis, try to chase this guy down if I can find him.149

After consulting with NEADS command, the crew commander issued the order at 9:23:"Okay . . . scramble Langley. Head them towards the Washington area.. . . [I]f they're there then we'll run on them.. . .These guys are smart." That order was processed and transmitted to Langley Air Force Base at 9:24. Radar data show the Langley fighters airborne at 9:30. NEADS decided to keep the Otis fighters over New York. The heading of the Langley fighters was adjusted to send them to the Baltimore area. The mission crew commander explained to us that the purpose was to position the Langley fighters between the reported southbound American 11 and the nation's capital.150

At the suggestion of the Boston Center's military liaison, NEADS contacted the FAA's Washington Center to ask about American 11. In the course of the conversation, a Washington Center manager informed NEADS: "We're looking-we also lost American 77."The time was 9:34.151This was the first notice to the military that American 77 was missing, and it had come by chance. If NEADS had not placed that call, the NEADS air defenders would have received no information whatsoever that the flight was even missing, although the FAA had been searching for it. No one at FAA headquarters ever asked for military assistance with American 77.

At 9:36, the FAA's Boston Center called NEADS and relayed the discovery about an unidentified aircraft closing in on Washington: "Latest report. Aircraft VFR [visual flight rules] six miles southeast of the White House. . . . Six, southwest. Six, southwest of the White House, deviating away." This startling news prompted the mission crew commander at NEADS to take immediate control of the airspace to clear a flight path for the Langley fighters: "Okay, we're going to turn it . . . crank it up. . . . Run them to the White House." He then discovered, to his surprise, that the Langley fighters were not headed north toward the Baltimore area as instructed, but east over the ocean. "I don't care how many windows you break," he said. "Damn it.. . . Okay. Push them back."152

The Langley fighters were heading east, not north, for three reasons. First, unlike a normal scramble order, this order did not include a distance to the target or the target's location. Second, a "generic" flight plan-prepared to get the aircraft airborne and out of local airspace quickly-incorrectly led the Langley fighters to believe they were ordered to fly due east (090) for 60 miles. Third, the lead pilot and local FAA controller incorrectly assumed the flight plan instruction to go "090 for 60" superseded the original scramble order.153

After the 9:36 call to NEADS about the unidentified aircraft a few miles from the White House, the Langley fighters were ordered to Washington, D.C. Controllers at NEADS located an unknown primary radar track, but "it kind of faded" over Washington. The time was 9:38.The Pentagon had been struck by American 77 at 9:37:46.The Langley fighters were about 150 miles away.154

Right after the Pentagon was hit, NEADS learned of another possible hijacked aircraft. It was an aircraft that in fact had not been hijacked at all. After the second World Trade Center crash, Boston Center managers recognized that both aircraft were transcontinental 767 jetliners that had departed Logan Airport. Remembering the "we have some planes" remark, Boston Center guessed that Delta 1989 might also be hijacked. Boston Center called NEADS at 9:41 and identified Delta 1989, a 767 jet that had left Logan Airport for Las Vegas, as a possible hijack. NEADS warned the FAA's Cleveland Center to watch Delta 1989.The Command Center and FAA headquarters watched it too. During the course of the morning, there were multiple erroneous reports of hijacked aircraft. The report of American 11 heading south was the first; Delta 1989 was the second.155

NEADS never lost track of Delta 1989, and even ordered fighter aircraft from Ohio and Michigan to intercept it. The flight never turned off its transponder. NEADS soon learned that the aircraft was not hijacked, and tracked Delta 1989 as it reversed course over Toledo, headed east, and landed in Cleveland.156 But another aircraft was heading toward Washington, an aircraft about which NORAD had heard nothing: United 93.

United Airlines Flight 93

FAA Awareness. At 9:27, after having been in the air for 45 minutes, United 93 acknowledged a transmission from the Cleveland Center controller. This was the last normal contact the FAA had with the flight.157

Less than a minute later, the Cleveland controller and the pilots of aircraft in the vicinity heard "a radio transmission of unintelligible sounds of possible screaming or a struggle from an unknown origin."158

The controller responded, seconds later: "Somebody call Cleveland? "This was followed by a second radio transmission, with sounds of screaming. The Cleveland Center controllers began to try to identify the possible source of the transmissions, and noticed that United 93 had descended some 700 feet. The controller attempted again to raise United 93 several times, with no response. At 9:30, the controller began to poll the other flights on his frequency to determine if they had heard the screaming; several said they had.159

At 9:32, a third radio transmission came over the frequency: "Keep remaining sitting. We have a bomb on board." The controller understood, but chose to respond: "Calling Cleveland Center, you're unreadable. Say again, slowly." He notified his supervisor, who passed the notice up the chain of command. By 9:34, word of the hijacking had reached FAA headquarters.160

FAA headquarters had by this time established an open line of communication with the Command Center at Herndon and instructed it to poll all its centers about suspect aircraft. The Command Center executed the request and, a minute later, Cleveland Center reported that "United 93 may have a bomb on board. "At 9:34, the Command Center relayed the information concerning United 93 to FAA headquarters. At approximately 9:36, Cleveland advised the Command Center that it was still tracking United 93 and specifically inquired whether someone had requested the military to launch fighter aircraft to intercept the aircraft. Cleveland even told the Command Center it was prepared to contact a nearby military base to make the request. The Command Center told Cleveland that FAA personnel well above them in the chain of command had to make the decision to seek military assistance and were working on the issue.161

Between 9:34 and 9:38, the Cleveland controller observed United 93 climbing to 40,700 feet and immediately moved several aircraft out its way. The controller continued to try to contact United 93, and asked whether the pilot could confirm that he had been hijacked.162 There was no response.

Then, at 9:39, a fourth radio transmission was heard from United 93:

Ziad Jarrah: Uh, this is the captain. Would like you all to remain seated. There is a bomb on board and are going back to the airport, and to have our demands [unintelligible]. Please remain quiet.

The controller responded: "United 93, understand you have a bomb on board. Go ahead." The flight did not respond.163

From 9:34 to 10:08, a Command Center facility manager provided frequent updates to Acting Deputy Administrator Monte Belger and other executives at FAA headquarters as United 93 headed toward Washington, D.C. At 9:41, Cleveland Center lost United 93's transponder signal. The controller located it on primary radar, matched its position with visual sightings from other aircraft, and tracked the flight as it turned east, then south.164

At 9:42, the Command Center learned from news reports that a plane had struck the Pentagon. The Command Center's national operations manager, Ben Sliney, ordered all FAA facilities to instruct all aircraft to land at the nearest airport. This was an unprecedented order. The air traffic control system handled it with great skill, as about 4,500 commercial and general aviation aircraft soon landed without incident.165

At 9:46 the Command Center updated FAA headquarters that United 93 was now "twenty-nine minutes out of Washington, D.C."

At 9:49, 13 minutes after Cleveland Center had asked about getting military help, the Command Center suggested that someone at headquarters should decide whether to request military assistance:

FAA Headquarters: They're pulling Jeff away to go talk about United 93.Command Center: Uh, do we want to think, uh, about scrambling aircraft?

FAA Headquarters: Oh, God, I don't know.

Command Center: Uh, that's a decision somebody's gonna have to make probably in the next ten minutes.

FAA Headquarters: Uh, ya know everybody just left the room.166

At 9:53, FAA headquarters informed the Command Center that the deputy director for air traffic services was talking to Monte Belger about scrambling aircraft. Then the Command Center informed headquarters that controllers had lost track of United 93 over the Pittsburgh area. Within seconds, the Command Center received a visual report from another aircraft, and informed headquarters that the aircraft was 20 miles northwest of Johnstown. United 93 was spotted by another aircraft, and, at 10:01, the Command Center advised FAA headquarters that one of the aircraft had seen United 93 "waving his wings." The aircraft had witnessed the hijackers' efforts to defeat the passengers' counterattack.167