Other reports appear to be consistent with our claim. For example, the document MFR 04017175 is the minutes from the interview by Team 7 and 8 to the United Airlines System Operations Control (SOC) Center and Crisis Center members on November 20, 2003 at the United Airlines SOC, Chicago, IL. Parts of this document are of extreme importance for our analysis and are reported below:

[U] When asked about

the technical capabilities of the ASD (airspace situational display)

program used by the dispatchers on their monitors to track planes, all

United representatives conferred that the program's display refreshes

every 60 seconds. If a plane was "squawking" a different code, the

United representatives did not believe that would change the appearance

of the track on the ASD. For instance, UAL 93, which was out of

communication for a longer time than UAL 175, appeared to be "coasting"

once the transponder was turned off. Barber did not think at the time

that modifying the transponder code would be apparent to dispatchers through the use of ASD.

[U]

McCurdy recollected that at the time of the crash into tower 2, the

display on Ballenger's monitor still showed UAL 175 at 31,000 ft, having

just deviated from the normal flight plan and heading into a big tum

back east. The track on Ballenger's ASD was frozen long after it was known the plane had crashed into tower 2.

[U] Rubie Green interjected that the program was designed to maintain a

tag on a flight as it moved across the map from center to center.

Various code changes would not affect the track as it appeared to the

dispatcher. McCurdy said that the ASD provides a rough track of a

plane's progress; minute alterations in the flight plan wouldn't be

reflected on the dispatchers display because such details only mattered

to the pilot and the air traffic controller. "The purpose of the track

is to keep the plane out of the path of a thunderstorm," McCurdy said.

[U] When they saw the second plane go in on CNN, instinctively Barber

thought it was UAL 175, but they did not a positive identification right

away. Because the scene caused much disturbance on the dispatch floor,

Barber told the staff to stay at their desks and focus on their jobs.

Barber noted that his log stated that at 8:20 a.m. (CT) UAL 175 was

confirmed.

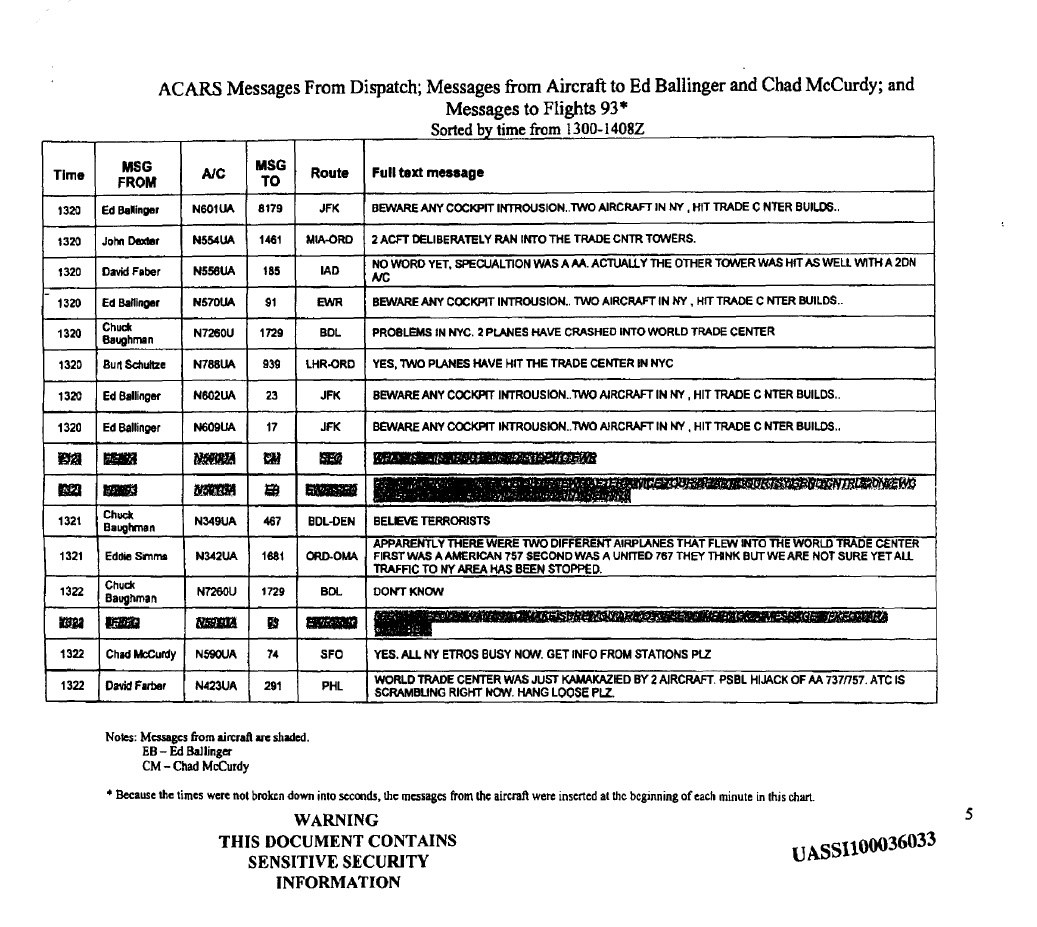

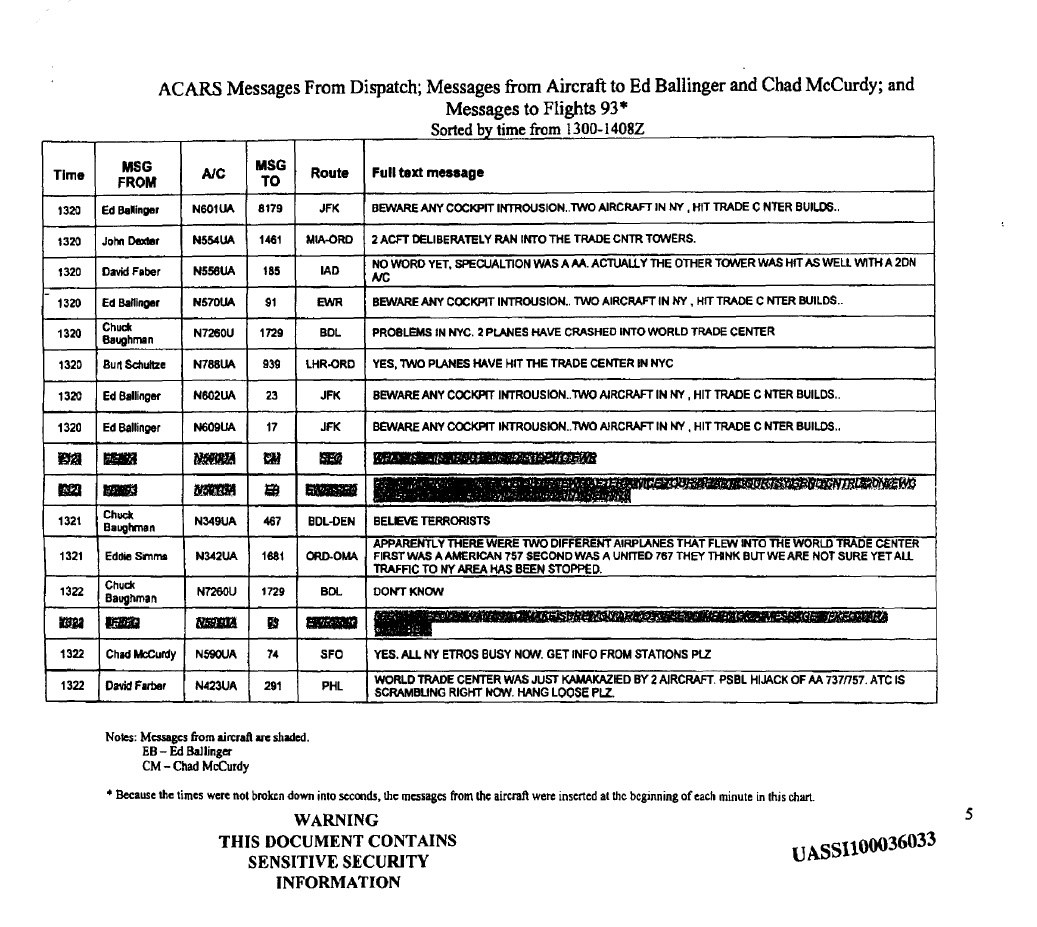

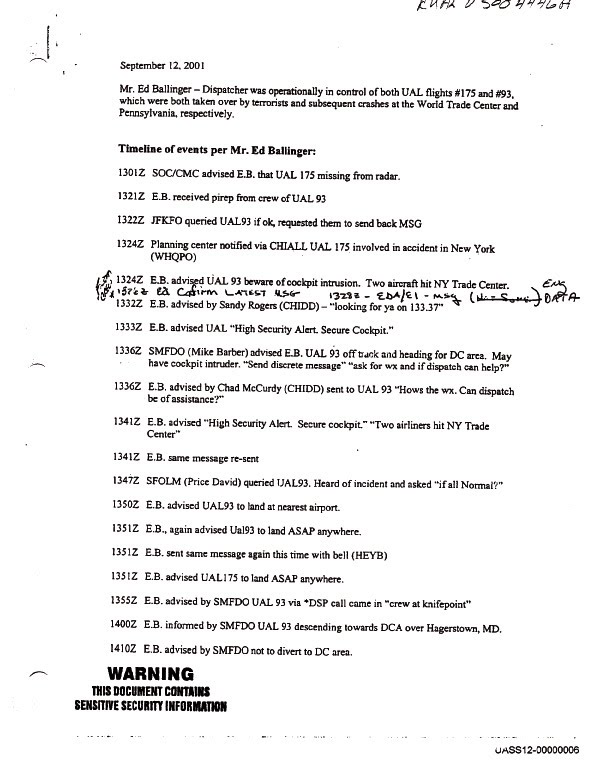

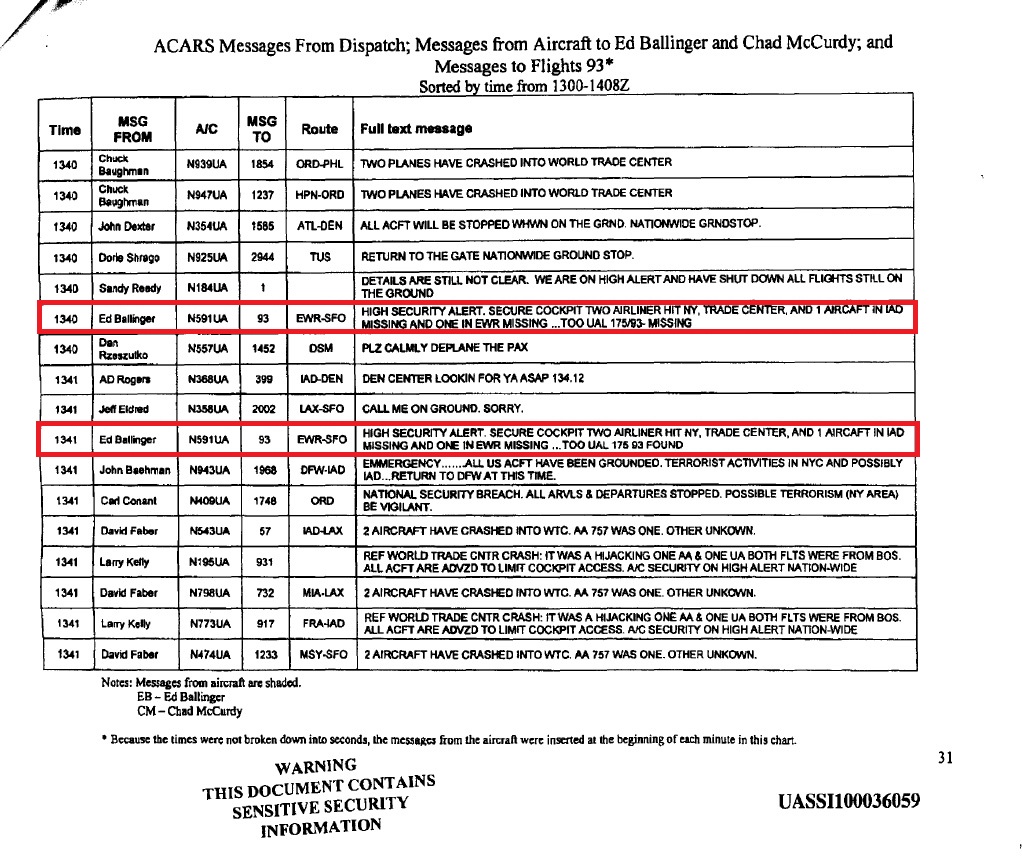

The last sentence in bold is pretty obscure, but extremely significant. The impression is that some information after the word "confirmed" was truncated or the sentence was intentionally left cryptic. Taking into a account that the location is United Airlines’ System Operations Control (SOC) center just outside Chicago, however, the reference to "his log" is a clear indication to Barber's ACARS log, which leads to conclude that at 8:20 Central Time (9:20 EDT) United 175 still appeared to be a "confirmed" aircraft according to the ACARS record and therefore could not be the same aircraft that every one at the SOC center had seen crashing against the South Tower on TV during the live CNN coverage. The entire sentence is of vital importance to understand the situation at the United SOC center around 9:20 EDT and may shed light to the subsequent behavior by Ballinger. Barber suggests that, when he saw the second plane hitting the tower in New York on TV, he instinctively suspected it could be United 175 because that flight had been already reported as hijacked and off-course, however this information was not confirmed by the ACARS log nor by the ASD monitor. If our interpretation is correct, then this is an additional evidence that no failure log had been yet reported by ARINC to the originator (UAL dispatch) 17 minutes after the alleged impact. This fact is pretty surprising if we consider that Ballinger had sent his first uplink to United 175 at 9:03 EDT ("How is the ride. Anything dispatch can do for you")

soon after being informed of the possible hijack and only instants after Sandy Rogers had sent another uplink at the same time ("NY aproach lookin for ya on 127.4"). According to

MFR 04017215, "Rogers-initiated message [was] not received by the aircraft". If this were true, then a failure report should have been sent to the UAL dispatch and Barber would have not seen United 175 as "confirmed" at 9:20 EDT. Both information are mutually exclusive. If an aircraft crashes, it just stops sending tracking messages to the ARINC CPS. The CPS keeps on searching for the aircraft for a maximum of 11 minutes, then generates a Reason Code 231 and sends a failure report back to the originator. But this is in conflict with an aircraft "confirmed". The most probable explanation for this discrepancy is that the information contained in MFR 04017215 is false (and remains unsubstantiated in any case). Both Rogers' and Ballinger's uplinks at 9:03 EDT were in fact received by the aircraft and this explains why Barber still saw the aircraft as confirmed in his own logs and also explains why the subsequent uplink sent by Ballinger at 9:23 EDT, as reported in the printout of his personal logs, shows two timestamps and has not the same format as the last message sent to United 93 at 10:21 EDT:

DDLXCXA CHIAK CH158R

.CHIAKUA DA 111323/ED

CMD

AN N612UA/GL PIT

- QUCHIYRUA 1UA175 BOSLAX

- MESSAGE FROM CHIDD -

/BEWARE ANY COCKPIT INTROUSION: TWO AIRCAFT IN NY . HIT TRADE C

NTER BUILDS...

CHIDD ED BALLINGER

;09111323 108575 0574

To make a long story short: such format requires either one of the following conditions: United 175 was airborne or had crashed less than 11 minutes before. Since the crash had allegedly occurred 20 minutes before, only the first condition applies here.

United 175 "was not acting appropriately"

Michael Ruppert dedicated a section of his book Crossing the Rubicon to Ed Ballinger. Parts of this section are relevant for our analysis and are reported below:

Suburban Flight Dispatcher to Recount Worst Day

Today, Ed

Ballinger will speak to a roomful of strangers about the one subject he

doesn’t care to discuss: The first two hours of his shift as a flight

dispatcher for United Airlines on the morning of September 11, 2001.

The

Arlington Heights resident and former United Airlines employee will

meet with a sub-committee of the 9/11 commission in Washington, DC, so

panel members can decide whether his testimony warrants his appearance

before the full commission.

Ballinger is there because he was in

charge of United Flights 175 and 93 when they crashed into the World

Trade Center and a field near Shanksville, PA.

Because

perhaps, just perhaps, offering his story will calm the whispering

thought that troubles him still: If he’d been told the full extent of

what was unfolding sooner that morning, he might have saved Flight 93.

“I

don’t know what [the panel appearance] is going to be,” he said Tuesday

after arriving in the capital. “They want to know what I did and why.

I’ve been told it’s not finger pointing. It’s just finding out what

happened.”

[...]

“When

September 11 came along, that morning, I had 16 flights taking off from

the East Coast of the US to the West Coast,” he said. “When I sat down,

these 16 flights were taking off or just getting ready to take off.”

[...]

Ballinger contacted all his flights to warn them. But United Flight 175 “was not acting appropriately.”

He

asked Flight 175 to respond. The pilot didn’t reply and Ballinger was

forced to conclude he’d been compromised and that he was rogue.

[This is exactly what long-standing FAA procedure told him to assume. See Chapter 17.]

By now, the situation was terribly different from previous hijackings Ballinger had handled. In two hours, he sent 122 messages.

“I

was like screaming on the keyboard. I think I talked to two flights

visually. The rest was all banging out short messages,” he said.

[...]

Ballinger said he was never the same after September 11, and was reluctant to return to work.

“That

first day, I’m lucky I didn’t hit anyone,” he said. “I drove through

every red light getting home as quickly as possible. I wanted to get

home and medicate myself.”

At work, he started second-guessing his own decisions and became, in his words, “ultra-ultra conservative.”

“I

came to a point where nothing was safe enough,” he recalled. “[I]

couldn’t even make a decision. It put you in jeopardy in every respect.”

At age 63, he was told to take a medical leave and long-term disability. He said he couldn’t do that. He was then asked if he could retire in six hours. A Social Security Administration psychiatrist put him on total disability.

"[United 175] was not acting appropriately" is a statement that may sound perfectly plausible to someone who never studied ACARS, especially if referred to an aircraft that has been hijacked and is off-course. For those who have knowledge about how ACARS communications between airline and aircraft work and about the timeline of the events, however, Ballinger's words sound sibylline at the very least.

To the benefit of those who are less familiar with ACARS, it should be reminded here that all messages sent by the airline to an aircraft (uplinks) are considered as delivered as long as no failure log is reported back to the originator (dispatcher). In other words, the lack of any

failure report is considered itself by the dispatcher as a confirmation that an uplink has been successfully delivered. Otherwise, whenever an aircraft fails to automatically acknowledge a message for any reason (including, of course, the case of a fatal accident), the ARINC CPS generates an error code and sends a failure report back to the dispatcher's printer and/or screen within some minutes. In this way, the dispatcher is notified that there is some problem with his aircraft and can take the appropriate steps to contact the aircraft through different channels. If United 175 had actually crashed at 9:03 EDT in New York, then Ballinger should not be

surprised that the cockpit was not replying to his uplinks or sending any other manual downlinks. Given the circumstances, this would be an expected behavior. Instead, Ballinger was possibly surprised that neither he nor any other dispatcher at United Airlines SOC center in Chicago had received any failure report from the ARINC CPS yet for two uplinks sent at 9:03 EDT and for one subsequent uplink sent at 9:23 EDT to United 175, as the statement by Mike Barber quoted above also suggests.

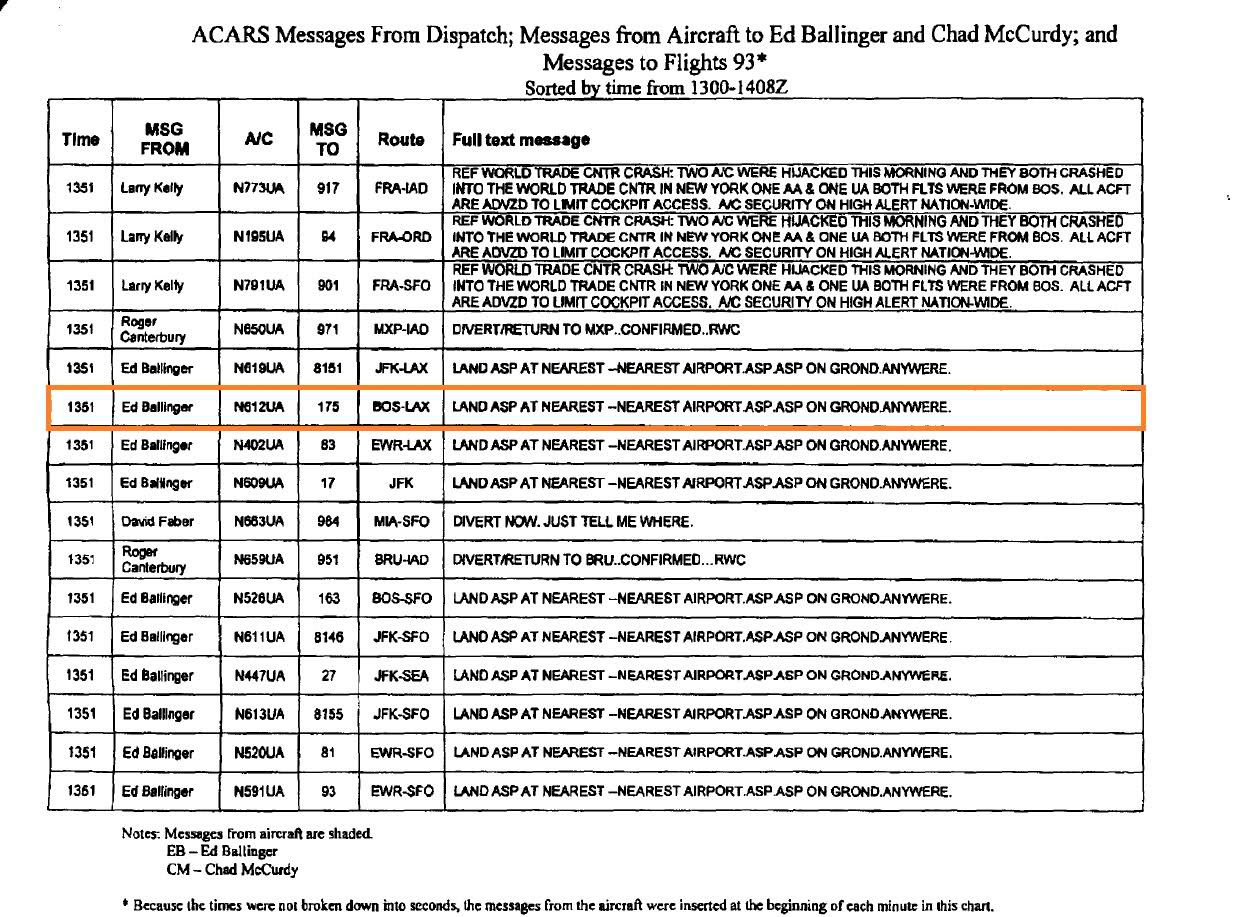

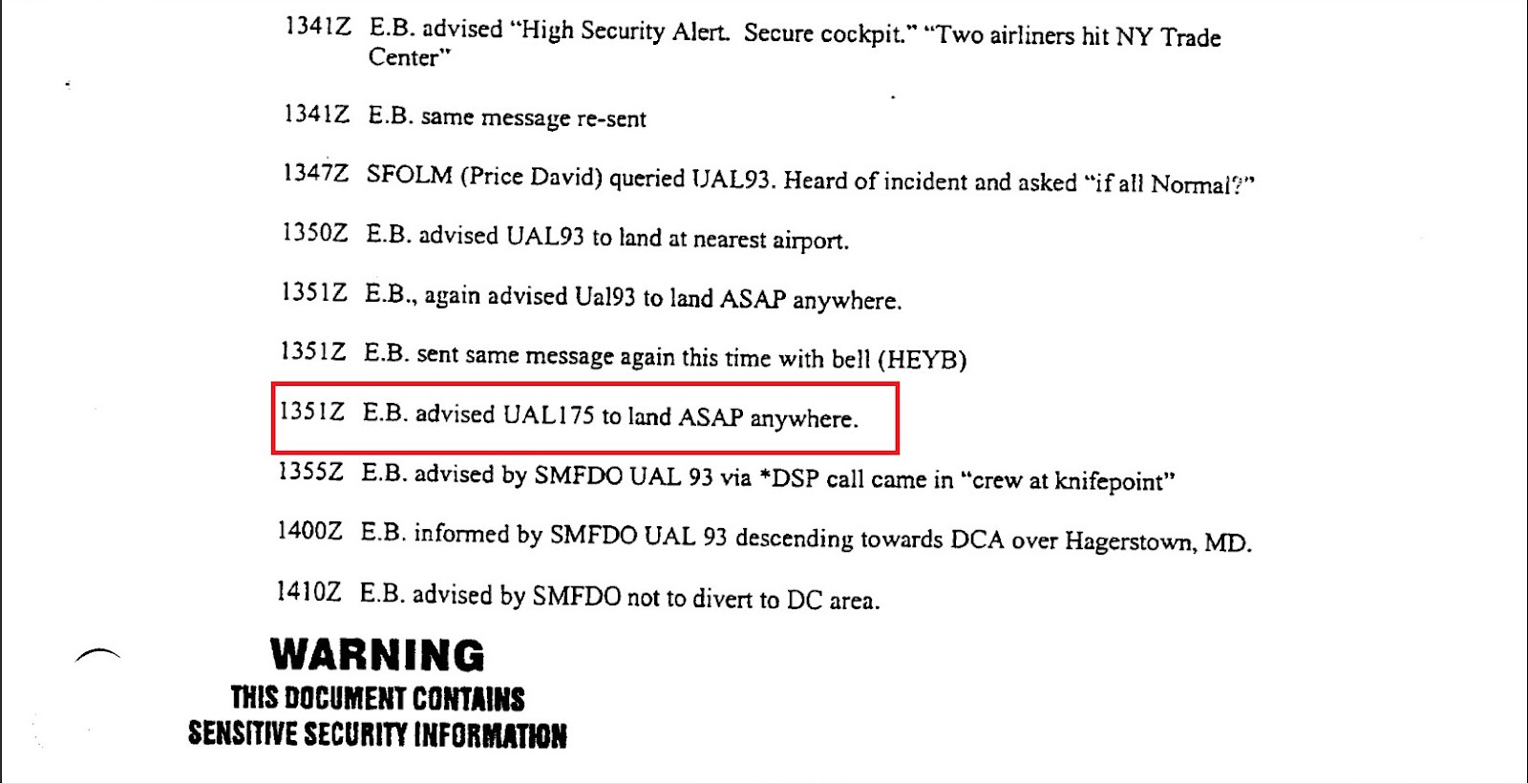

While the available documentation does not allow us to conclusively prove this assertion, everything points consistently into the same direction. Ballinger was being told by the TV and by the United management that his aircraft had crashed, but his ACARS log and his ASD were not confirming that, therefore he desperately kept on trying to contact his aircraft until 9:51 EDT. As a very experienced dispatcher, Ballinger knew that, if his aircraft had really crashed, this would reflect in his ACARS log with one or more appropriate failure reports for any unsuccessfully delivered uplink. As we have seen in both messages sent to United 93 between 9:40 EDT and 9:41 EDT, at that time Ballinger knew that two aircraft had suffered a fatal accident in New York, still he was not entirely convinced that one of them was actually United 175, as reported officially. If he were, then he would not consider United 175 first as "missing" and later as "found" at around 9:40 EDT and in no circumstances would he contact the aircraft again at 9:51 EDT. At the current state of the research, this appears to be the only plausible explanation for his otherwise sudden behavior and the only plausible explanation why, years after, he stated that United 175 "was not acting appropriately" as reported by Michael Ruppert.

Conclusion

For most, if not all the questions raised by this article no conclusive evidence can still be presented after almost 11 years. Several official records are still classified, other have been apparently declassified but are of dubious authenticity or have been surprisingly released with shaded information. Finding the "truth" within this tangle of omissions, conflicting reports, missing logs, different "FLoc" numbers etc. is beyond us. While we won't speculate here about the possible reasons for such omissions and discrepancies, it is an unquestionable fact that Ed Ballinger sent an uplink to United 175 at 9:51 EDT. The evidence comes from two official declassified records whose authenticity is beyond any doubt. Our only goal here is to present facts and raise questions which are still unanswered:

- if United 175 had crashed at 9:03 EDT against the South Tower, then why did the aircraft still appear as "confirmed" in Barber's log at 9:20 EDT?

- why does the log for the uplink sent by Ballinger to United 175 at 9:23 EDT show two timestamps although 20 minutes had already elapsed since the time of the alleged crash? After twenty minutes from the crash, we would expect that the ARINC CPS would react with a Reason Code 231 (see for example the first ICPUL block for American 77 at 10:00 EDT, 22 minutes after the alleged crash against the Pentagon), what would result in turn in a failure report on Ballinger's printer/screen and a log with one only timestamp, such as the last message sent to United 93 at 10:21 EDT. What does such discrepancy suggest?

- how could possibly Ballinger send an uplink to United 93 at 9:40 ending with "United 175/93 missing" and one minute later another message to United 93 ending with "United 175/93 found" if he had not received in the meanwhile (from some unidentified source) information suggesting that United 175 was in fact still airborne?

- why did Ballinger send another uplink to United 175 at 9:51 EDT, 48 minutes after the alleged crash, 28 minutes after sending the previous uplink (which apparently had not yet produced any failure report) and 27 minutes after being officially notified about the crash by Andy Studdert? Why should he urge an aircraft already declared as 'crashed' to land at the nearest airport?

- and finally, what did Ballinger actually mean with "[United 175] was not acting

appropriately"? How could a dispatcher with 44 years of professional career possibly overlook a failure report and keep on trying to contact his aircraft for almost one hour after the alleged crash time if he hadn't some information that led him to conclude that the aircraft was in fact not "lost"? The whole UAL dispatch in Chicago was focused on both United aircraft considered as hijacked. How could possibly all of them miss a failure report in their logs?

The supporters of the official story may argue again that the decision of sending a late uplink to United 175 may be simply the result of Ballinger's haste to get the word out or the result of the conflicting information he was receiving on the morning of 9/11. While this is possible in theory, then the question arises why did the Commission not bother to address this specific log during Ballinger's interview on April 14, 2004. Why is this log missing in the UAL record of Ballinger's logs released in 2009 under FOIA? Why are several pages from that document missing? Why are the logs for United 175 completely missing in the so called "Printout of ARINC logs" made public in December 2011?

The answers to the above questions will probably shed light one day to what really happened to United 175. Understanding what really happened to United 175 is the key to understand what really happened on 9/11.